| Escanaba Trough |

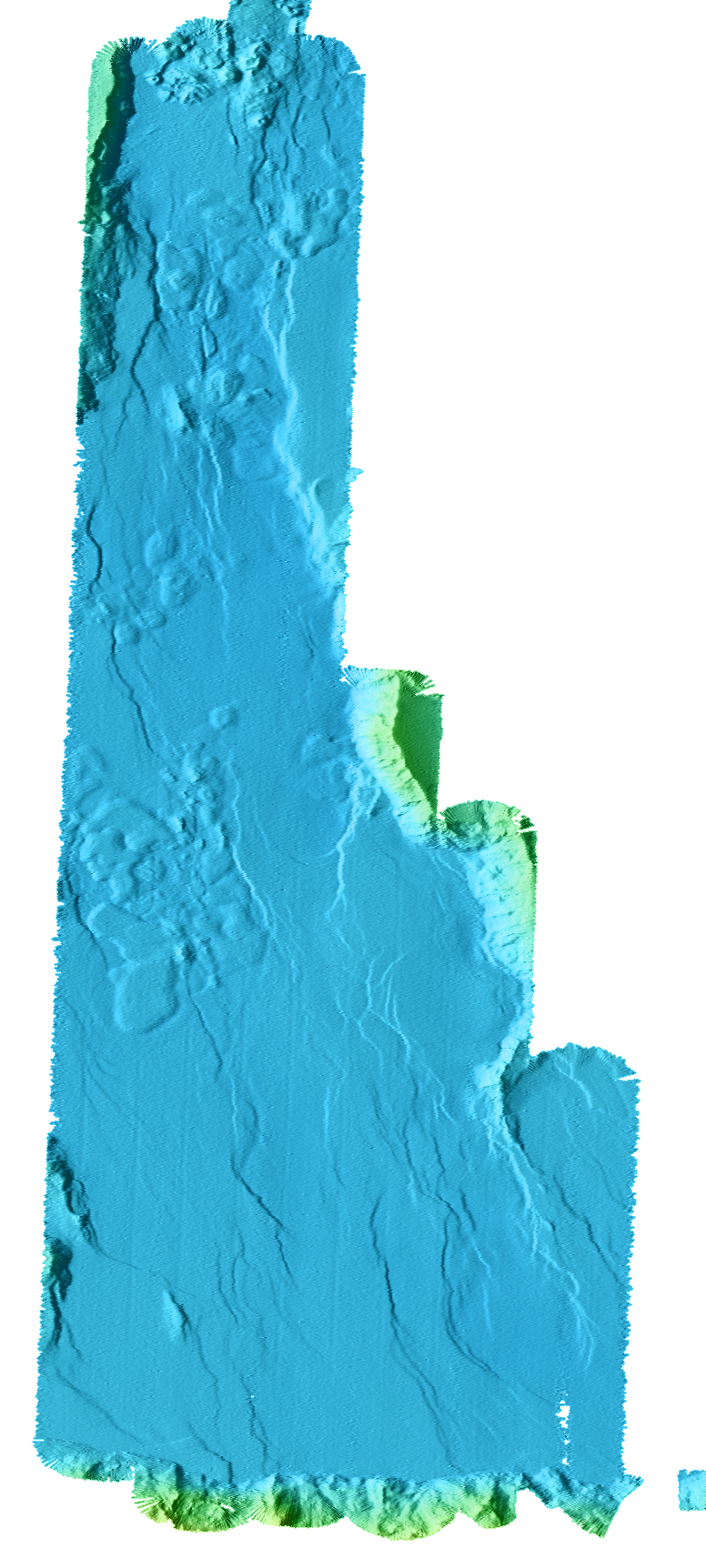

from http://www.mbari.org/data/mapping/seamounts/escanaba.htm |

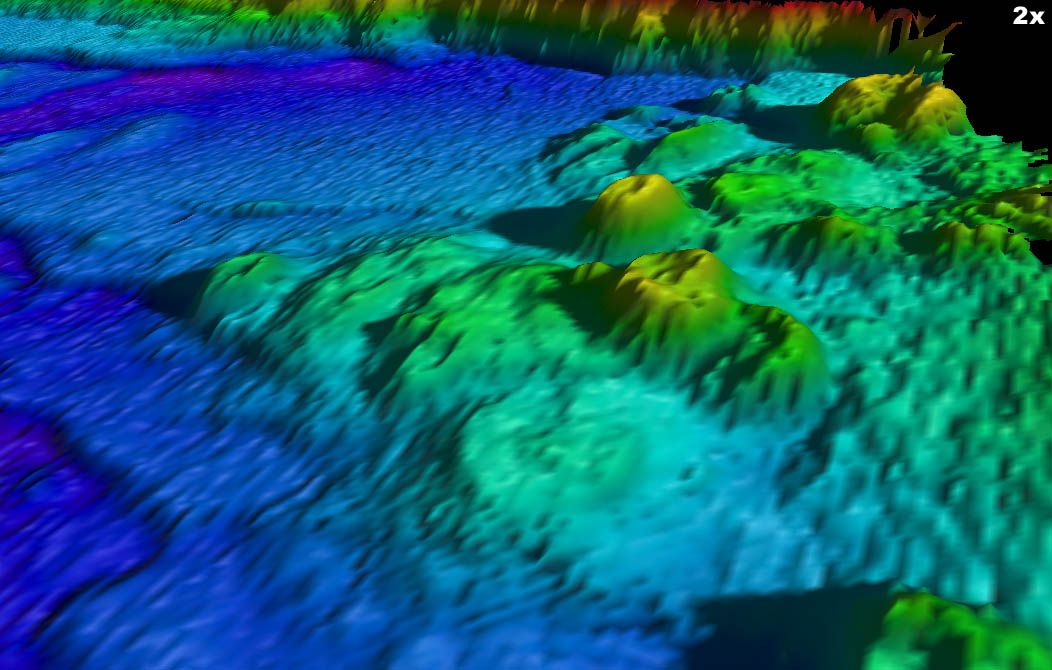

http://www.mbari.org/data/mapping/seamounts/escanaba.htm - Northern end of Escanaba Trough showing volcanic cones, from the east |

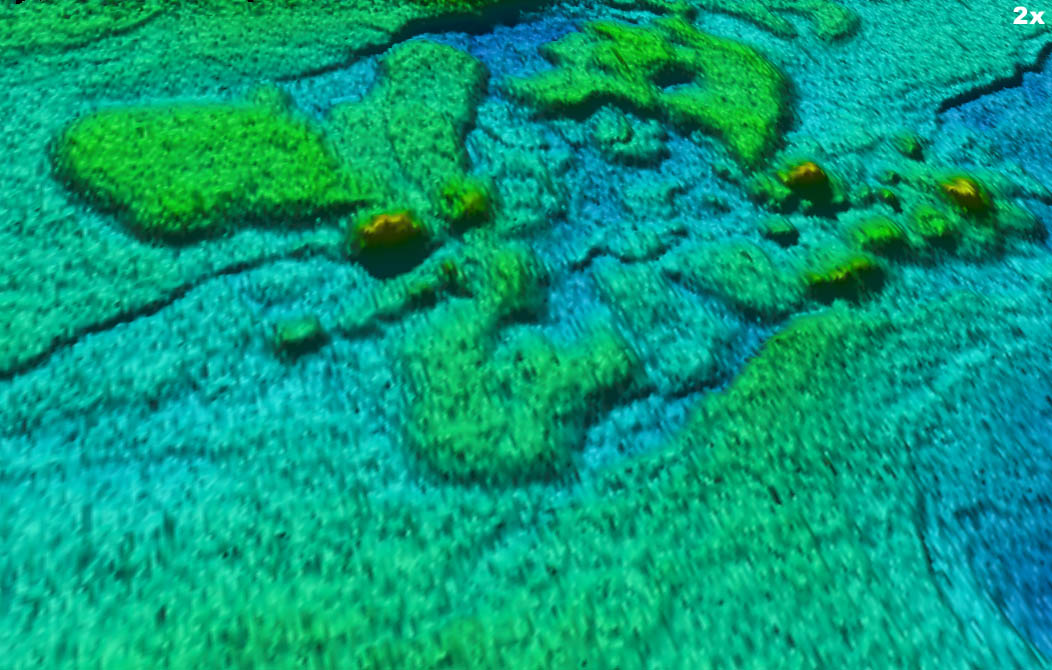

http://www.mbari.org/data/mapping/seamounts/escanaba.htm - Southern Escanaba Trough from the southeast |

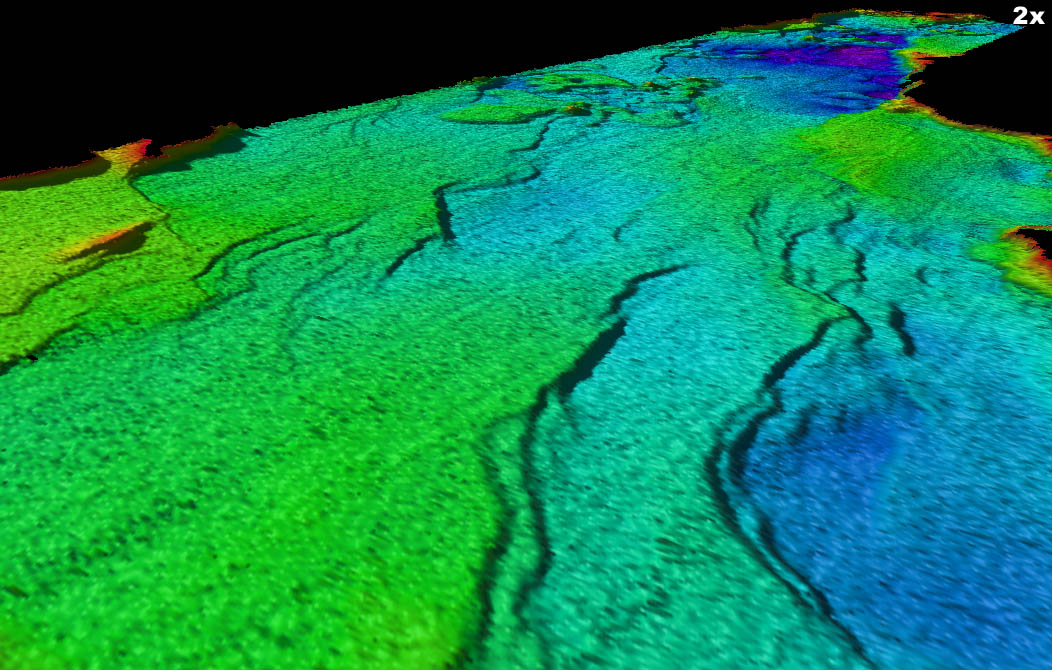

http://www.mbari.org/data/mapping/seamounts/escanaba.htm - Southern Escanaba Trough showing faults in sediment, from the southeast |

http://marine.usgs.gov/fact-sheets/gorda/ -Gerneralized geologic map of Escanaba Trough. Massive sulfide deposits and hot springs occur near volcanic centers |

Craggy sulfide mound formed on the sediment-covered floor of Escanaba Trough. Photograph taken from submersible Alvin, courtesy of Robert Zierenberg -http://marine.usgs.gov/fact-sheets/gorda/ |

Clusters of tube worms and white crabs on a sulfide mound in the Escanaba Trough at a depth of 3,230 meters. View is approximately 0.5 meters across. Photograph taken from submersible Alvin, courtesy of Bruce Taylor |

From MBARI - http://www.mbari.org/data/mapping/seamounts/escanaba.htm

Escanaba Trough is the southern sediment-filled portion of the Gorda mid-ocean Ridge. It extends northward from the Mendocino Fracture Zone about 130 kilometers, to the southernmost right-lateral offset on Gorda Ridge, at about 41�35�N. The spreading rate along this part of the Gorda Ridge is about 2.3 centimeters per year. The valley floor is 3-5 kilometers wide at the northern end and widens to about 18 kilometers near the Mendocino Fracture Zone. South of about 41�8�N, the axial valley is filled by as much as 500 meters of sandy turbidites. These turbidites derived from the Columbia River drainage during floods produced by outbursts from glacial lakes, (including lake Missoula) during the Late Pleistocene (Zuffa et al., 2000). The sediment fill is pierced by a series of discrete volcanic centers that uplifted the sediment over sills and erupted some lava flows on the seafloor (Morton et al., 1987). The sediments are also disrupted by faulting within the trough, indicating deformation and extension continued after deposition of most of the sediment. Uplifted sediment hills above some of the sills have been used to estimate the timing and amount of vertical motion using the thickness of specific turbidite units (Normark, and Serra, 2001). The volcanic centers have been mapped in some detail using towed photographic systems and observations from submersibles (Ross et al., 1994). The lavas recovered have been studied to evaluate assimilation of sediment during shallow crustal storage and fractional crystallization (Davis et al., 1994, 1998). These uplifted hills are also the site of extensive hydrothermal mineralization, although active vents are restricted to a single region near 41�N named NESCA (Morton et al., 1994). NESCA and SESCA are acronyms for Northern and Southern ESCAnaba, two regions where extensive study has been conducted. A single volume (Morton et al., 1994), published as U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2022 in 1994, summarizes nearly all previous work. Subsequent to these studies, the Ocean Drilling Program drilled a series of holes at the NESCA site to investigate hydrothermal circulation and massive sulfide formation (Fouquet et al., 1998). Numerous papers on the results of the drilling program can be found in the ODP Initial Reports volume 169.

The new high-resolution bathymetry shows the faults that offset the sediment fill in Escanaba Trough in great detail. In addition, it is evident that there are two types of sills present: the small deep sills that uplift sediment hills, as described by Morton et al.(1987, 1994) and a second type that are shaped like large lobate flows. These flow-shaped sills are apparently much shallower in the sediment and have uplifted large regions by 30-50 meters. Recent remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dives on the tops of several of these sills shows extensive hydrothermal deposits and outcrops around the margins of the sill where the sediment has slumped.

From Dr. Randolph Koski - http://marine.usgs.gov/fact-sheets/gorda/

The Escanaba Trough of southern Gorda Ridge is a slowly-spreading ocean ridge that provides a unique perspective on the formation of world-class metal deposits.

Offshore of northern California and Oregon, the 3,300-meter deep trough extends northward from the Mendocino Fracture Zone for 150 kilometers. It is covered for most of this length by as much as 1,000 meters of sediment shed from the Pacific continental margin of the United States. The combination of this sediment blanket (a thermal insulator), buried volcanic centers (a source of heat), and an abundant supply of fluid (seawater) results in favorable conditions for formation of large sediment-hosted polymetallic sulfide deposits. Analogous deposits on land are rich in precious and base metals and can be very large. Escanaba Trough''s massive sulfide deposits may also have substantial size and contain high grades of gold, silver, copper, and zinc, as well as lesser amounts of metals such as antimony, bismuth, lead, cobalt, and tin. Although it is unlikely that deposits in the Escanaba Trough will be mined in the near future, understanding how and where such deposits form is a critical step in successfully exploring for land-based analogues.

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) researchers are developing models for tectonic and hydrothermal processes that form the Escanaba Trough sulfide deposits.

Because of the slow spreading rate of Gorda Ridge, it forms a deep trough that allows thick accumulations of sediment. Active volcanic centers within these sediments induce circulation of heated seawater through the permeable sand-rich sediment layers. Volcanic intrusions cause uplift of sediment blocks; fault zones along the boundaries of these blocks serve as pathways for fluid flow to the seafloor. The circulating seawater reacts with volcanic rock and sediment to produce an acidic fluid capable of leaching and transporting metals. As the hot, buoyant, metal-enriched fluid rises to the seafloor, it is neutralized by mixing with seawater to form metal sulfide precipitates that collect to form a massive sulfide deposit. Active fluid-discharge sites also sustain robust biological communities that include worms, snails, clams, and crabs. Yet many questions remain about fluid pathways in the sediment and underlying oceanic crust, the reaction between these heated waters and the sediment, structural controls for fluid transport, factors that control composition and distribution of sulfide deposits, and the nature of biological habitation at active vents.

USGS scientists hope to learn more about Escanaba Trough by conducting more detailed studies.

Earlier studies in Escanaba Trough revealed the presence of large polymetallic sulfide deposits enriched in copper, gold, silver, and other metals that may be comparable in size and metal content to analogous deposits on land. However, information about the three-dimensional distribution and composition of the mineral deposits and sediment alteration, fluid flow paths, and magmatic and structural evolution of the trough are incomplete, especially in areas peripheral to sites of concentrated study. High-resolution seismic reflection surveys are planned to obtain three-dimensional information and high-resolution sidescan sonar surveys can image the distribution of deposits and related geologic features. In addition to geophysical studies, other future work includes photographic surveys using a towed camera sled and core and dredge sampling conducted from a surface ship. Collaborative programs with other government agencies (e.g., the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Navy, and the Geological Survey of Canada) and university researchers will utilize submersibles and remotely-operated vehicles for detailed observations, mapping, and sampling around vent sites. In 1996, USGS geologists will participate in Leg 169 of the Ocean Drilling Program which plans to drill into hydrothermally-active sulfide deposits in Escanaba Trough

USGS workers are studying the role of bacteria in the deposition and oxidation of sulfide minerals.

USGS researcher Robert Zierenberg and his colleagues have begun investigating the role of seafloor microbes in forming and altering metal sulfide deposits. Microbial organisms at deep sea hydrothermal vents, such as those in the Escanaba Trough, have evolved over millions of years and have adapted to an environment that has high acidity and high concentrations of metals not unlike conditions that exist in some sites contaminated by past mining activity. These vent bacteria appear to be capable of selectively extracting metals such as silver and arsenic from solution. Bacteria may also have a major role in sulfide oxidation. Perhaps these microbes could be adapted for bio-mining or bio-remediation of acid mine waters, thereby providing a natural solution to an anthropogenic problem. Pharmaceutical companies have already patented DNA polymerase enzymes from deep-sea vent bacteria for use in the rapidly growing biotechnology industry.

The investigation of ocean ridges is relevant to our country''s long-range resource picture and to the development of mineral-resource models.

The stable supply of mineral commodities is essential to the economic health of the United States and a sustainable standard of living for its people. In the context of ever-increasing environmental and economic constraints on land mining, the deep marine environment of ocean ridges within the United States Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) will become increasingly attractive as a future source of base and precious metals. Meanwhile, observations of mineral-deposit formation on the seafloor in "real time" are paying dividends in developing genetic and exploration models for analogous ore deposits on land.