| Deep-sea organisms |

|

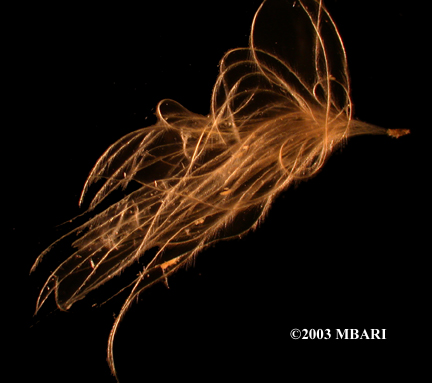

Pogonophoridae |

Laqueus californianus |

Oligochaeta |

|

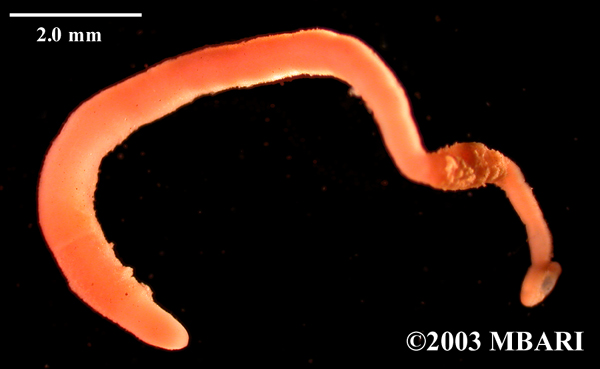

Nemetea |

Nemertea proboscis |

Anemone |

|

Anemone |

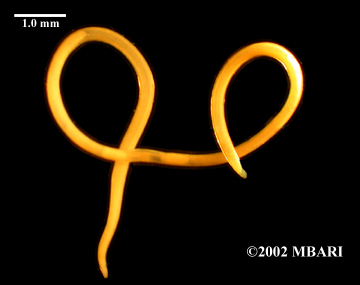

Nematode |

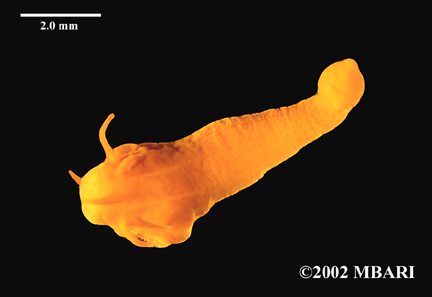

Sipunculid |

|

Crinoid |

Zooanthids |

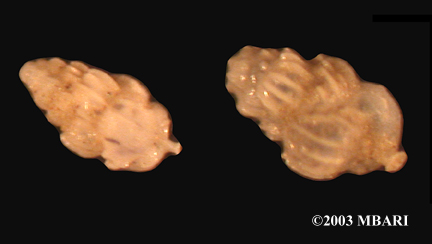

Foraminiferans-Rupertina stabilis |

|

Foraminiferans-Rupertina stabilis |

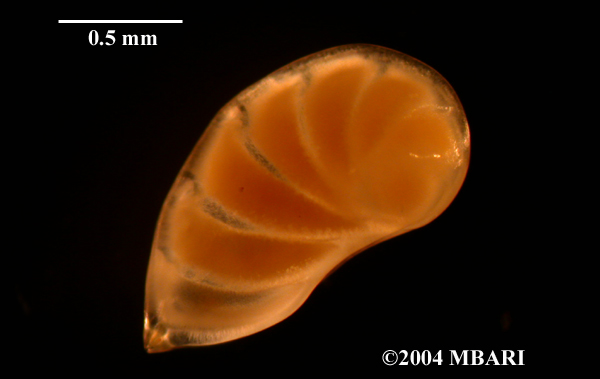

Foraminiferans-Uvigerina feregrina |

Foraminiferans-Bolivina spissa |

|

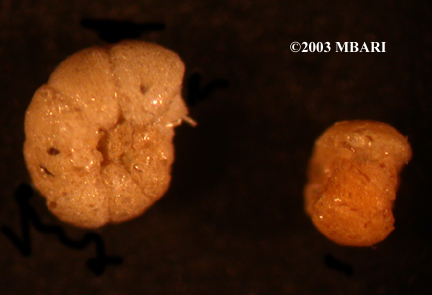

Foraminiferans-Globobulimina sp |

Foraminiferans-?Bulimera barbata |

Foraminiferans-Epistominella pacifica |

|

Foraminiferans-Bulininella tenuata |

Foraminiferans-Epistominella smithi |

Foraminiferans-?Haplophragmoides sp. |

|

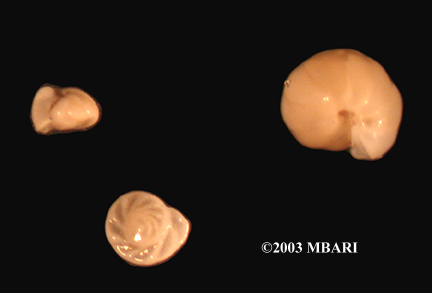

Foraminiferans-Epistominella pacifica |

Foraminiferans-?Gyroidina altiformis |

Foraminiferans-Foram |

|

Foraminiferans-Foram |

Xenophyophore (Psamminidae) |

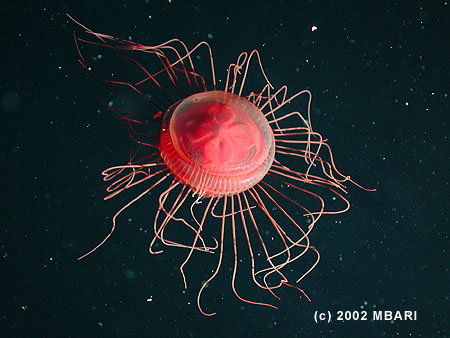

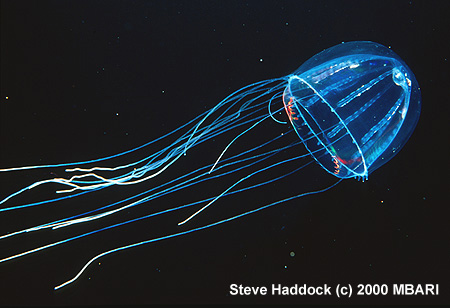

Atolla jelly.MBARI researchers photographed this scyphomedusa or crown jelly offshore of Monterey Bay at about 965 meters (almost 3,200 feet) below the sea surface. At this depth, the seawater is about four degrees Centigrade (39 degrees Fahrenheit) and contains very little oxygen. It is thought that the reddish color of many deep-sea jellies helps to hide the glow of any bioluminescent prey that may be inside their stomachs |

|

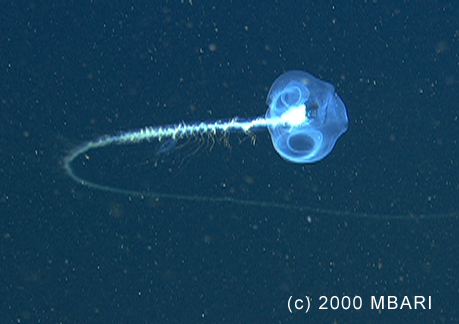

Growing over 40 meters long, siphonophores in the genus Praya may be some of the longest animals in the world. At the "front" of the animal are two swimming bells whose rhythmic contractions propel a long chain of feeding and reproductive organs through the water like a freight train. Hanging down from this chain (but not visible in this photo) are long tentacles with stinging cells that create a "curtain of death" for small jellies, crustaceans, and even fish. Siphonophores are very abundant at times in Monterey Bay and may be the top predators in some midwater food webs |

Goiter Sponge,Yellow goiter sponges, such as this Heterochone calyx on Pioneer Seamount, can grow to well over a meter (3 feet) across. Like most sponges, they eat by filtering microscopic bits of debris from the seawater that flows past them. MBARI researchers often see "forests" of sponges on the upper portions of seamounts, where eddying ocean currents may concentrate food particles. Even after large sponges die, their skeletons may survive for years on the seafloor. On some parts of Pioneer Seamount and other seamounts, new sponges grow on generations of dead ones, eventually forming "sponge reefs." |

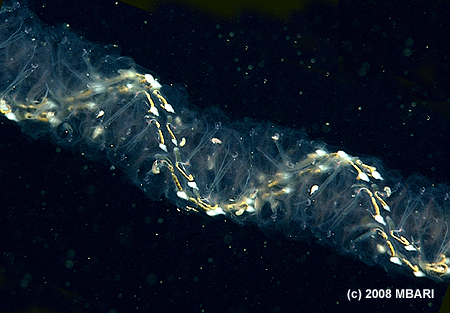

Salp chain.Salps are gelatinous animals that live in the open ocean, but are closely related to the "sea squirts" (tunicates) seen in tidepools. Colonial salps such as this one in the genus Heliosalpa often form long chains, with new animals budding off from others in the chain. By rhythmically contracting their bodies, salps propel themselves through the water and pump water through their guts, filtering out microscopic algae and other tiny organisms for food. This allows them to swim and eat at the same time. With such a simple feeding strategy, salps can multiply very rapidly when they have plenty of food. Most salps are found within 100 meters of the sea surface, where there is enough sunlight for algae to grow. Along the Central California coast, salps are typically seen in fall, when warm, open-ocean water flows toward shore |

|

Apolemia.Siphonophores like Apolemia are deep-sea predatorslying in wait for unfortunate animals to blunder into their curtain of stinging cells. Their diet can include tiny crustaceans such as copepods, fish, and even other siphonophores. Although many siphonophores eat whatever they can catch, others are specialists. Some use lures to attract specific prey. Others deploy their tentacles in elaborate feeding shapes, like coils or J-postures. These feeding shapes must constantly be re-set as the animal sinks through the water |

Sea Nettle Monterey -http://ocean.si.edu/ocean-photos/cameraman-sea-nettles |

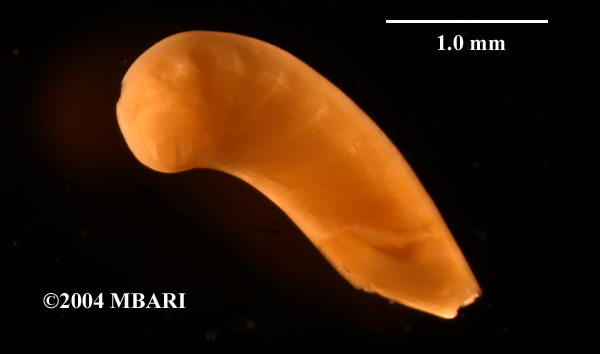

Beroe.This animal, which looks like a watery, pink football, is actually an fierce deep-sea predator (though it is only a few inches long). It is a ctenophore (pronounced "teen-o-four") called Beroe abyssicola. Ctenophores are gelatinous animals that swim by waving tiny hair-like projections called "ctenes." Beroe abyssicola also has tiny hairs that act like "teeth" that help it grab onto its prey. When Beroe bumps into another jelly, it grabs on using these teeth, opens its mouth (at left) really wide, and tries to swallow its prey whole- |

|

Colobonema.This beautiful jelly in the family Colobonema is a fast-moving deep-sea predator, but it also has several strategies to avoid being preyed upon. It''s transparent body blends in with the surrounding seawater. But if it is attacked, the jelly can shed one or more of its tentacles, which glow brightly, distracting its attacker. The discarded tentacles apparently grow back over time. |

Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria form whitish or yellowish mats up to a meter across. These bacteria typically live in areas where hydrogen sulfide concentrations are so high that nothing else can survive -http://www.mbari.org/news/homepage/2005/noseeps.html#aboutcbcs |

Vesicomyid clams often live in areas where hydrogen sulfide is available just below the sediment surface. They obtain all their nutrition from bacteria in their gills, which consume hydrogen sulfide. With a steady supply of hydrogen sulfide, these clams may live for up to a century and grow to over 15 cm long |

|

Vestimentiferan worms. Tangled communities of tubeworms live in many of Monterey Bay''s chemosynthetic biological communities. Like Vesicomyid clams, these tubeworms obtain nutrition from sulfur-loving bacteria in their guts. Their long roots can burrow up to 2 meters into sediment or bedrock in search of methane and hydrogen sulfide for their bacterial food providers |

Vestimentiferan tubeworms growing from a small notch in the wall of Monterey Canyon. These chemosynthetic animals live off of hydrogen sulfide in the sediment, which would be toxic to most other animals. Below the tubeworms are several anemones attached to the canyon wall - http://www.mbari.org/news/homepage/2005/noseeps.html#aboutcbcs |

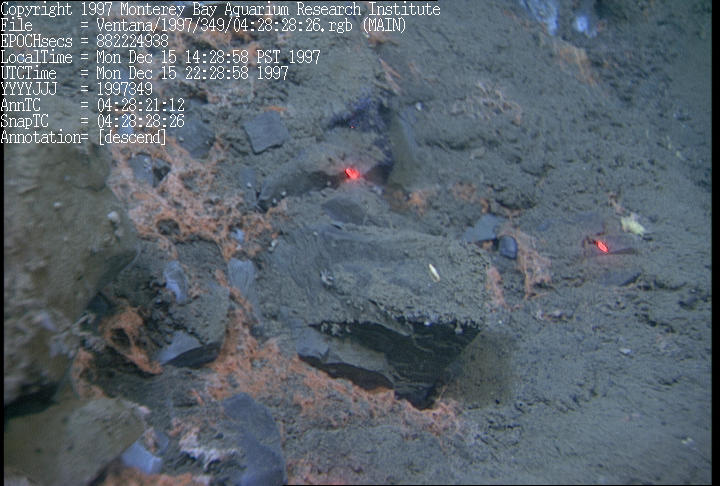

Bacterial mat (orange) fueled by chemical-rich fluids seeping through the walls of Monterey Canyon Image © MBARI 1997-http://www.mbari.org/volcanism/Margin/Marg-Hydrates.htm |

from MBARI - http://www.mbari.org/benthic/other.htmlhttp://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/07/060702085004.htm -Jellyfish-Like Creatures May Play Major Role In Fate Of Carbon Dioxide In The Ocean

In the May issue of Deep Sea Research, scientists report that salps, about the size of a human thumb, swarming by the billions in hot spots may be transporting tons of carbon per day from the ocean surface to the deep sea and keep it from re-entering the atmosphere. Salps are semi-transparent, barrel-shaped marine animals that move through the water by drawing water in the front end and propelling it out the rear in a sort of jet propulsion. The water passes over a mucus membrane that vacuums it clean of all edible material.

The oceans absorb excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, some from the burning of fossil fuels. In sunlit surface waters, tiny marine plants called phytoplankton use the carbon dioxide to grow. Animals then consume the phytoplankton and incorporate the carbon, but most of it dissolves back into the oceans when the animals defecate or die. The carbon can be used again by bacteria and plants, or can return to the atmosphere as heat-trapping carbon dioxide when it is consumed and respired by animals.

Biologists Laurence Madin of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and Patricia Kremer of the University of Connecticut and colleagues have conducted four summer expeditions to the Mid-Atlantic Bight region, between Cape Hatteras and Georges Bank in the North Atlantic, since 1975. Each time the researchers found that one particular salp species, Salpa aspera, multiplied into dense swarms that lasted for months.

One swarm covered 100,000 square kilometers (38,600 square miles) of the sea surface. The scientists estimated that the swarm consumed up to 74 percent of microscopic carbon-containing plants from the surface water per day, and their sinking fecal pellets transported up to 4,000 tons of carbon a day to deep water.

Salps swim, feed, and produce waste continuously, Madin said. They take in small packages of carbon and make them into big packages that sink fast.

In previous work, Madin and WHOI biologist Richard Harbison found that salp fecal pellets sink as much as 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) a day. The scientists also showed that when salps die, their bodies also sink fastup to 475 meters (1,575 feet) a day, faster than most pellets. If salps are really a dead-end in the food web and remain uneaten on the way down, they could send even more carbon to the deep.

Salpa aspera swims long distances down in daylight and back up at night in what is known as vertical migration. Madin, Kremer and colleagues Peter Wiebe and Erich Horgan of WHOI and Jennifer Purcell and David Nemazie of the University of Maryland found that the salps stay at depths of 600 to 800 meters (1,970 to 2,625 feet) during the day, coming to the surface only at night.

At the surface, Madin said, salps can feed on phytoplankton. They may swim down in the day to avoid predators or damaging sunlight. And swimming up at night allows them to aggregate to reproduce and multiply quickly when food is abundant.

Because of this behavior, salps release fecal pellets in deep water, where few animals eat them. This enhances the transport of carbon away from the atmosphere.

In 2004 and 2006, Madin and Kremer studied salp swarms in a different ecosystem, the Southern Ocean near Antarctica. Some scientists have reported larger salp populations there in warmer years with less sea ice. If this proves true, and if Antarctica''s climate warms, salp swarms could have a greater effect on phytoplankton and carbon in the Southern Ocean ecosystem.

Funding for this study was provided by the National Science Foundation, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Access to the Sea program at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

see animal gallery -http://www.mbari.org/news/feature-image/feature-image-gallery.html

http://www.mbari.org/news/feature-image/beroe.html

Animal Gallery

http://faculty.washington.edu/cemills/Ctenophores.html

Pelagic Tunicates

The Watery World of Salps

Siphonophores