| Sedimentary Basin: Extension.....Lengthening.....Subsidence.....RSL Rise.....Sedimentation |

|

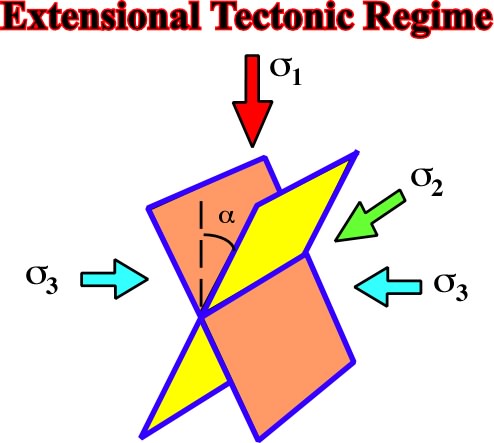

Fig. 162- In an extensional tectonic regime, the maximum effective stress (1) is vertical. The sediments are lengthened by the development of normal faults, which strike parallel to the medium effective stress, i.e. 2. However, the presence of normal faults is not by itself enough to indicate a "stage of regional extension". Indeed, normal faults associated with processes of compaction, shale tectonics, salt tectonics, etc., do not indicate a stage of regional extension |

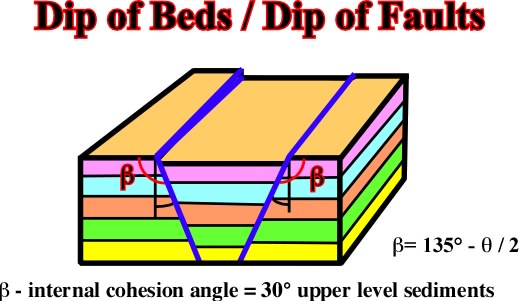

Fig. 163- In the upper levels of the ground, the dip of conjugated normal faults ranges between 60-70░, while the dip of conjugated reverse faults ranges between 30-40░. The dip strike slip faults is sub-vertical. Such a criterion (Anderson''s law) is particularly useful in geological interpretation of seismic lines. For that, a roughly depth conversion at natural scale (1:1) is often enough. Vertical normal faults do not exist, even if, locally, the dip can be near 90є. In fact, as normal faults are developed in order to length the sediments, a vertical normal fault is against all Nature''s laws. It cannot length or short and, in addition, it implies a crucial volume problem, since there is no space on the ground (void) allowing a vertical throw |

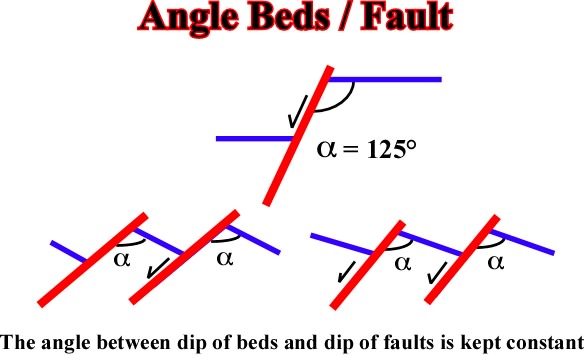

Fig.164- As illustrated on this sketch, the angle between a normal fault plane and the beds composing the footwall and the hangingwal is keep roughly constant, either when the throw changes or or when the sediments are tilted. |

|

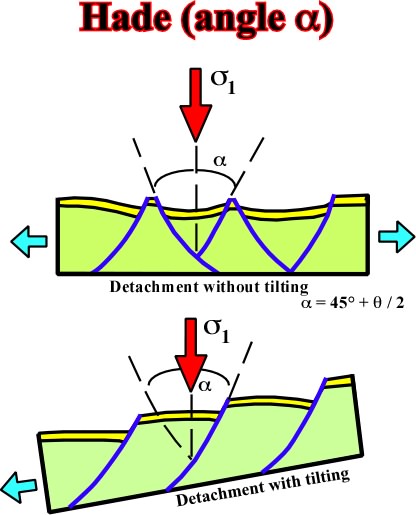

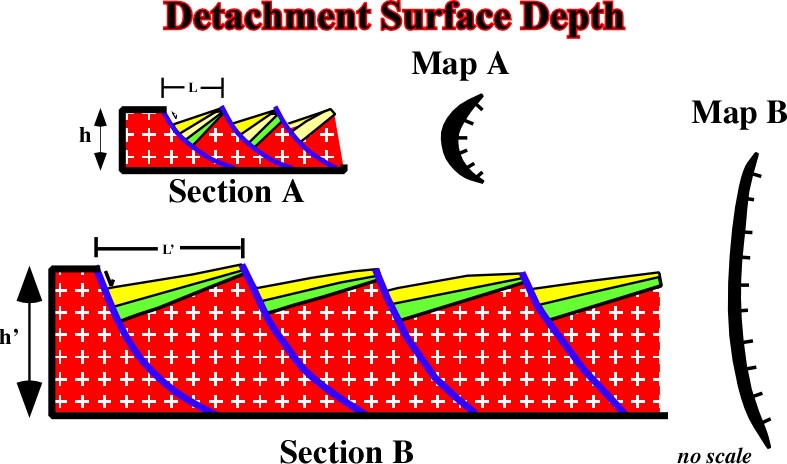

Fig. 165- In normal faulting, the hade, which is the complement of the dip, is constant. In the upper sketch, where the detachment plane is not tilted, it value is represented by the angle a ( more or less equal to 45є plus half of the internal cohesion angle b). As illustrated in the lower sketch, the hade is the same, even when the detachment plane is tilted. |

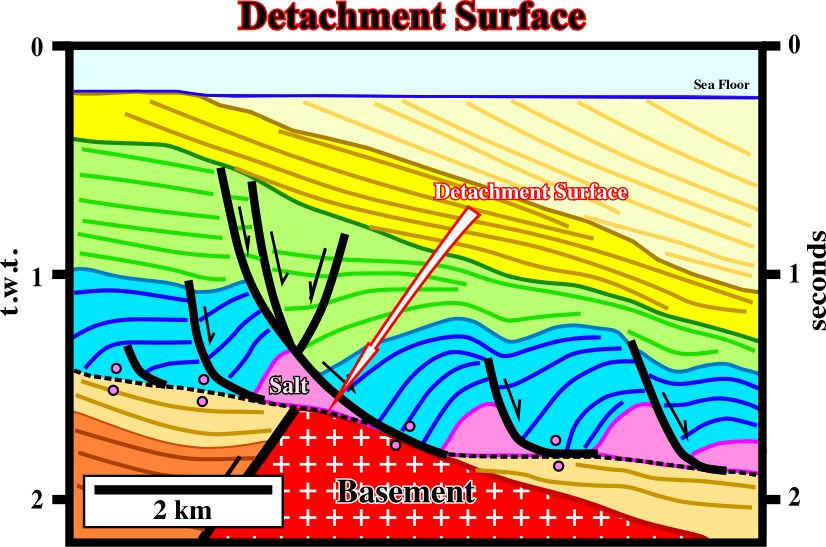

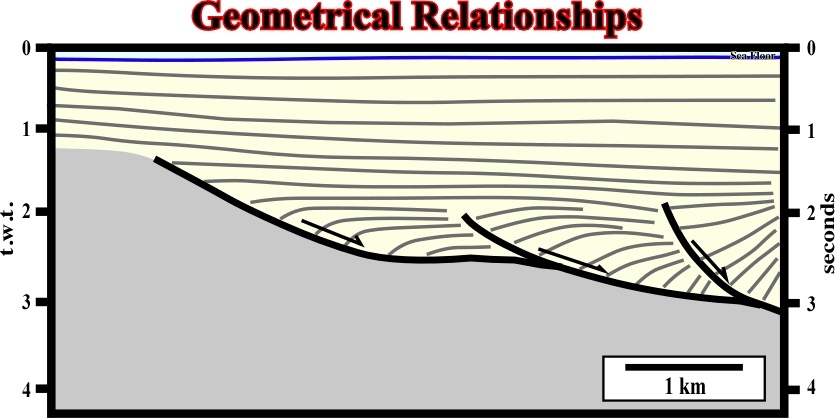

Fig. 166- Larger are the fault blocks, smaller is the rotation of the blocks and so lower is the detachment surface and less curvilinear is the cartography of the fault plane. Such empiric statement can easily be corroborate on seismic lines, particularly those shot in areas affected by a thin skinned extension, as illustrated below (fig. 167). |

Fig. 167- On this seismic line a detachment surface associated with the base of a mobile layer (allochthonous salt) created a sharp tectonic disharmony. The sediment overlying the tectonic disharmony were deformed in a complete different way of those below it. The overlying sediments were lengthened by curvilinear normal faults dipping downdip with a more or less constant angle (the hade increases slightly in depth, but not too much). The fault blocks show roughly the same rotation and, in a map, the fault planes have more or less the same geometry. |

|

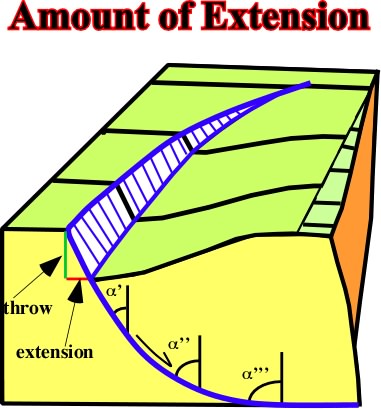

Fig. 168- In listric normal fault, the change of vertical displacement (throw) is associated with the rotation of the downthrown blocks and with the amount of extension. At the ends a fault the extension is zero. Notice how the hade increases with the depht pf the fault plane. It reaches 90║ when the detachments surface becomes horizontal. |

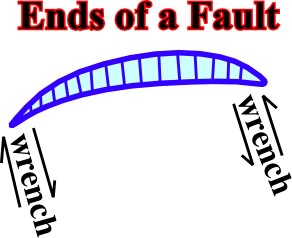

Fig. 169- As at the ends of a fault there is no extension, and so, no throw, the presence of a unique fault is impossible since it creates differential wrench movements. In other words, to extent (lengthen) a certain area of 10%, for instance, several normal faults are necessary to avoid wrench deformations., i.e. to create an homogeneous extension |

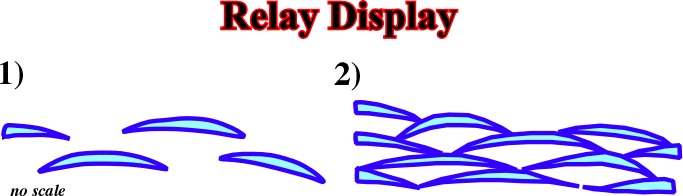

Fig. 170- The large majority of the normal faults are curvilinear. When they look rectilinear is just a question of scale. So, one can say when normal faults are display in relay, the lengthening of the area is homogeneous. Indeed, since along the 3, the sum of the extension created by each fault is constant. In other words, each end of a fault (extension zero) is relayed by the maximum throw (maximum of extension) of the next downdip fault, as illustrated above and below (fig. 171). |

|

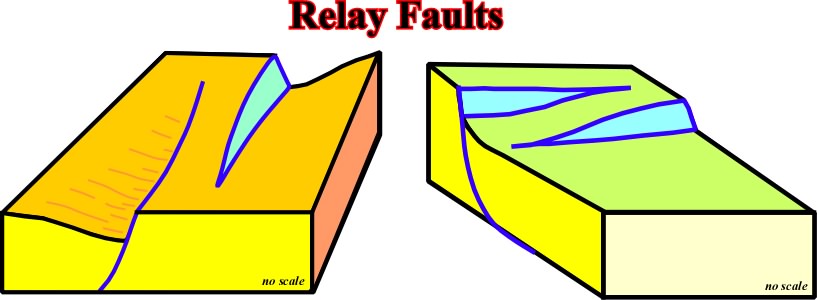

Fig. 171- In relay faults the maximum of extension of a fault fits with the minimum of extension of the nearby fault, in order to give an homogeneous extension of the area, i.e. avoid differential wrench movements near the ends of the faults (see fig. 172). |

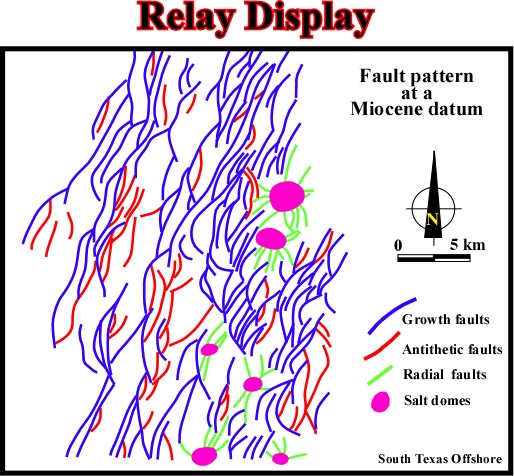

Fig. 172- On this structural sketch, the growth faults (in bleu) are displayed in relay, which gives an homogeneous seaward extension. Note the antithetic faults (red), as well as the radial faults (green) associated wont the salt domes. The radial faults were developed by local extensional tectonic regimes (2 = 3) at the top of the diapiric structures. |

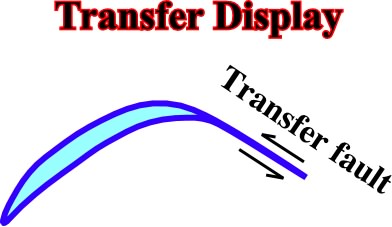

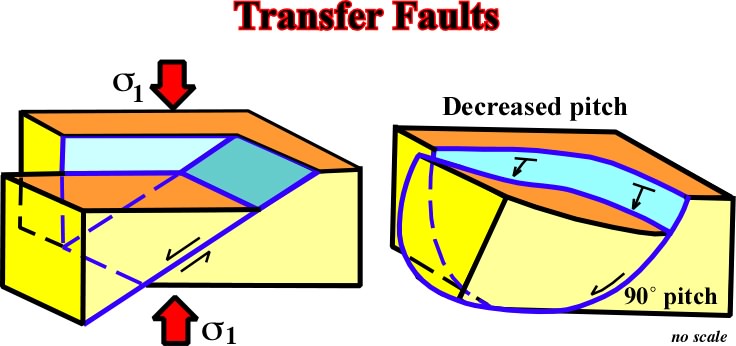

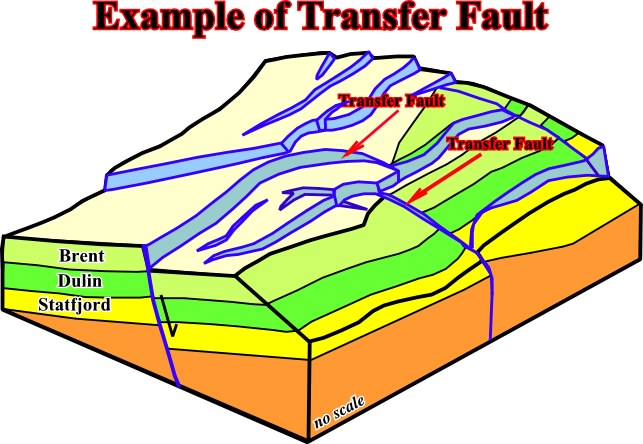

Fig. 173- In a transfer display, as illustrated on this sketch, at the end of a fault, extension is transfer to a nearby normal fault, buy a a vertical and rectilinear zone called, often, transfer fault, as shown in block diagrams below (fig.174). |

|

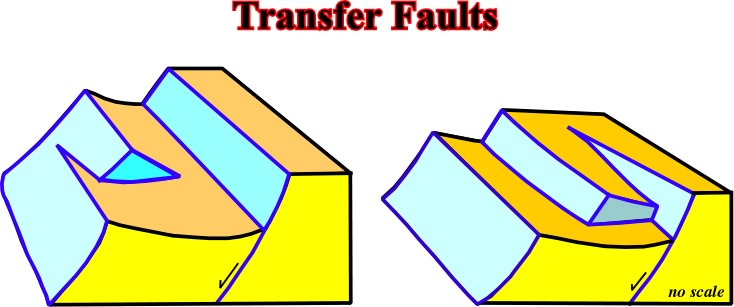

Fig. 174- Transfer fault allows extension to be transferred to other normal faults. In these examples,one can see that they are extensional strike slip faults wit a vertical or almost vertical fault plane (see fig. 175). |

Fig. 175- In these block diagrams, based on seismic data of offshore Japan, it is easy to understand the role of transfer faults in the lengthening of the non-Atlantic type and Atlantic-type divergent margins (fig. 176). |

Fig. 176- In North Sea, detailed structural maps show very often that extensional accommodation was obtain by the development of transfer faults as in this particularly example coming from a Total''s field. |

|

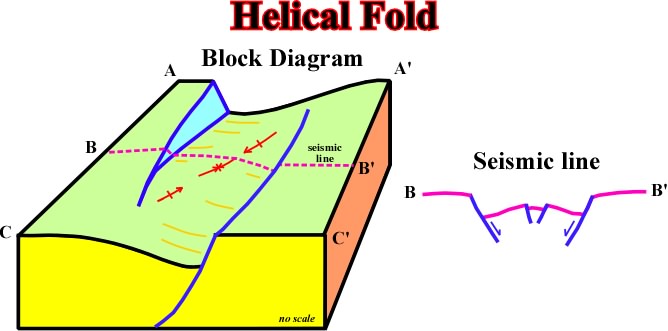

Fig. 177- This block diagram illustrated an helical fold, which is often used by funny geologists to farmout areas characterized by an absence of hydrocarbon traps. Indeed, as one can easily notice, in 3D, the apex of the structure, bounded by the opposite vergence normal faults, is a structural low and not a high. |

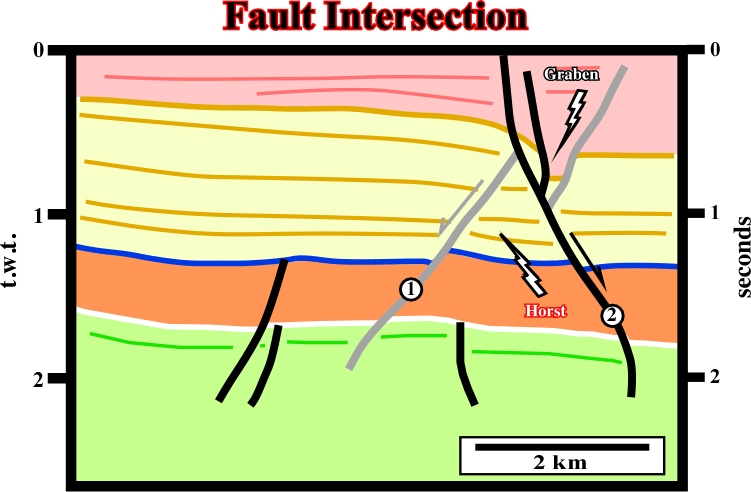

Fig. 178- This seismic line illustrates the displacement of a normal fault by another normal fault of different age. Admittedly, the faults dipping to the left (in green) are older than the faults dipping to the right (in red), i.e. the green faults were displaced downward and rightward by the younger faults. Such a displacement created, in the same vertical, a graben above a horst. This geometry, called by some as "X-faults" is typical of such intersections faults. |

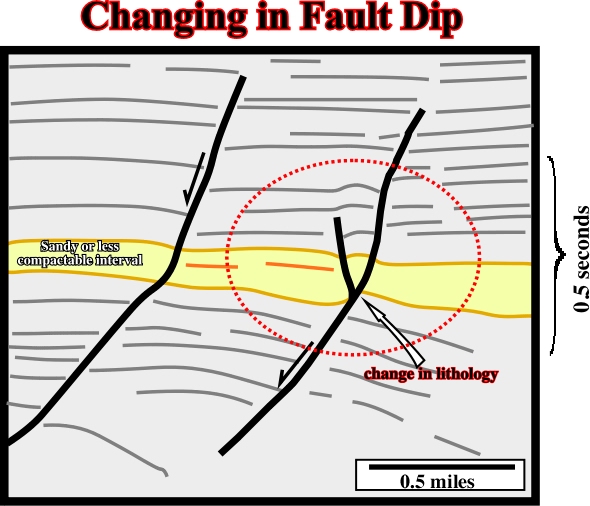

Fig. 179- As illustrated on this seismic line, the dip of a fault change all along the fault plane. Such a change is mainly induced by compaction of the sediments which implies a pre-compaction faulting (see below, (i) no planar faults). |

|

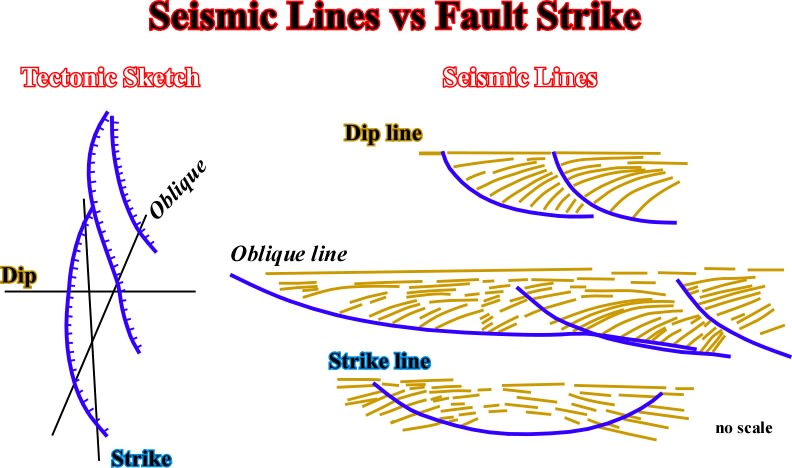

Fig. 180- On a seismic line, the geometry of the reflectors is largely depend of the angle between the profile and the strike of the faults. The more representative geometry is the one recognize on dip lines, i.e. lines perpendicular to the strike of the fault and sediments. Indeed, in oblique and strike lines, the geometric relationships between the reflectors themselves or between the reflectors and the disconformities are apparent as illustrated on the seismic line below (fig.181). |

Fig. 181- On this slalom seismic lines, i.e. a non rectilinear line, the faults planes are intersect at different angles. So, the geometry of the reflectors, particularly in the hangingwal are quite different. The more representative is the one where the rotation of the hangingwall is more homogeneous and higher, that is to say the hangingwall on the right. |

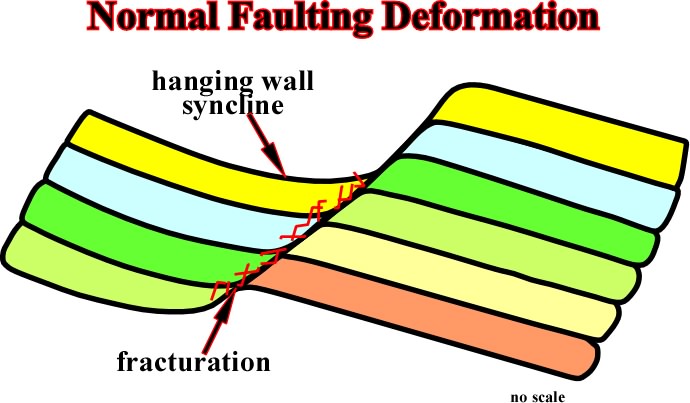

Fig.182- In a normal fault, due to the relative downward movement of the hangingwall, the bedding planes are slightly deformed and fractures, often to fill the space created by the lengthening. |

|

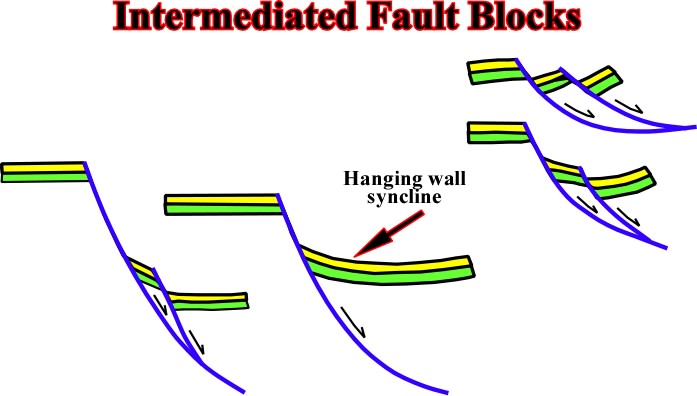

Fig. 183- Very often, in order to accommodate the hangingwall sediments to the new volume conditions, intermediated fault blocks are developed. They are limited down dip by the major fault and due to the rotation of the major faulted blocks, they can dip toward the downthrown block, or in opposite sense (fig. 184). |

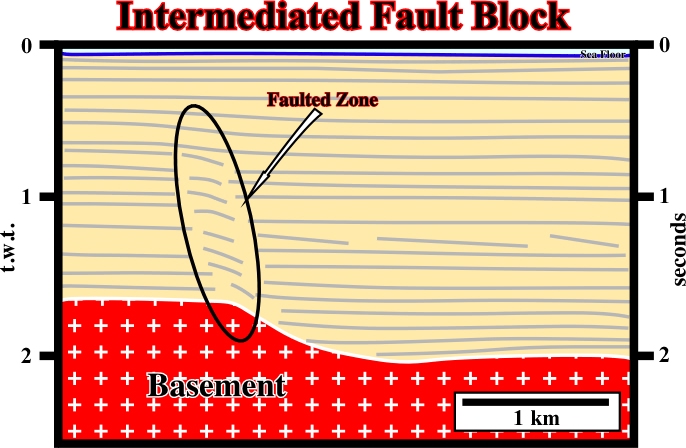

Fig. 184- On this seismic line, the sediments were lengthened by a normal faulting. However, due to the lack of rotation of the hanging wall, the development of an intermediated fault block was necessary to solve volume problems, i.e. potential voids. |

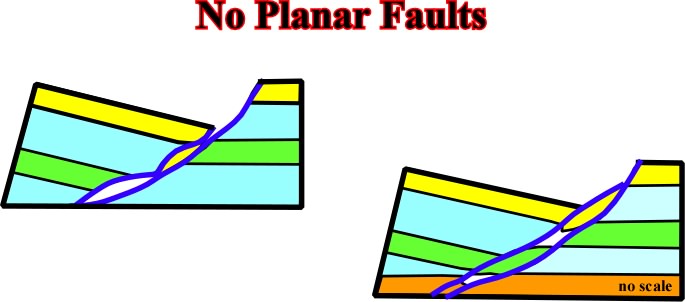

Fig. 185- As illustrated, in no planar faults, volume problems can be solved by the dev elopement of a gauge zone between the fault blocks. However, the majority of the sediments of such a deformed zone come from the hangingwall |

|

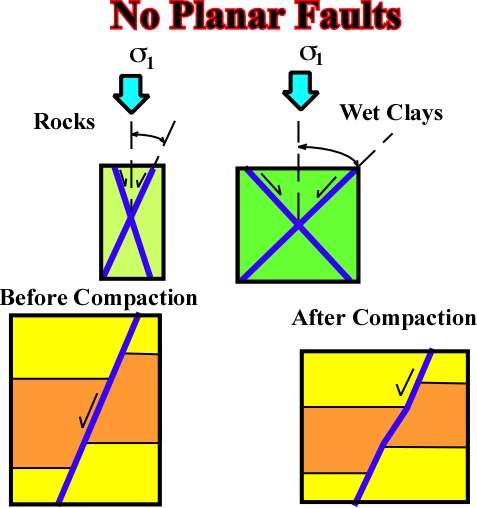

Fig. 186- As illustrated, the angle between two conjugated normal faults depends either on the sediment''s rheology or on the differential compaction. Indeed, when normal faulting is pre-compaction the dip of the fault planes, after compaction, can change a lot. It depends on then compactability of the sediments. Admittedly, shales are much more compatable than sands, so, the dip of fault planes in sandy sediments will high han in shaly facies (fig. 187). |

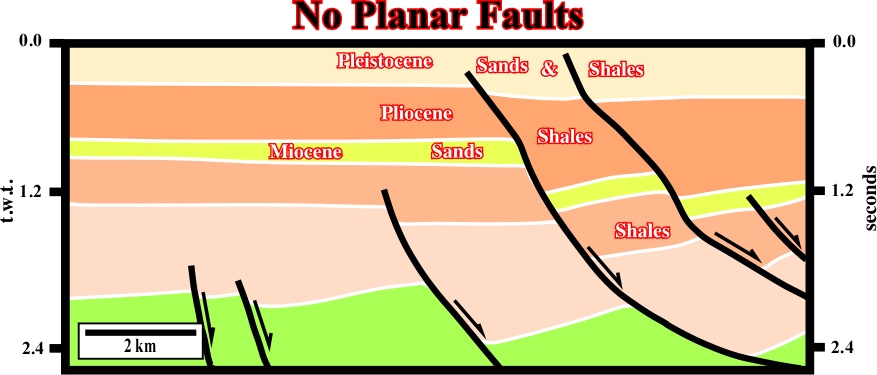

Fig. 187- On this seismic line from the Gulf of Mexico, the interpretation is redundant. The geometry of the fault planes clearly indicates a change in facies (sand / shales) of the stratigraphic intervals. In fact, the lithology of the Neogene sediments of the Gulf Coast is fundamentally an interbedding of shales and sands, and the sandy interval are lesser compatable than the shaly. |

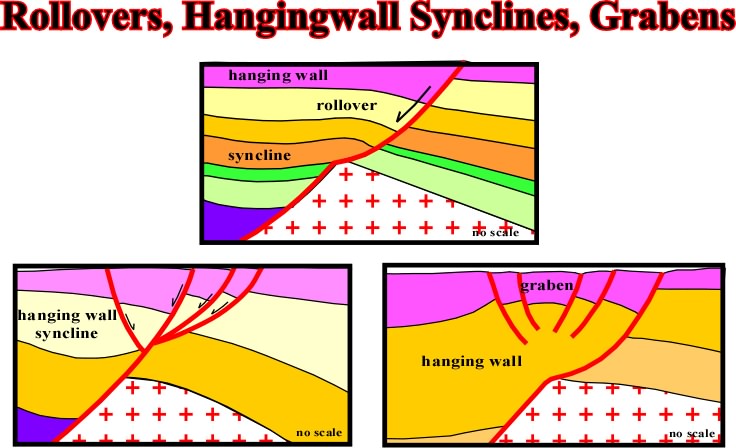

Fig. 188- The change in lithology, between the basement and sediments, in the footwall created in the hangingwall a volume problem. Subsequently, the sediments were obliged to extend to avoid potential voids. THus rollovers, hangingwall synclines and graben were developed in the downthrown block. |

|

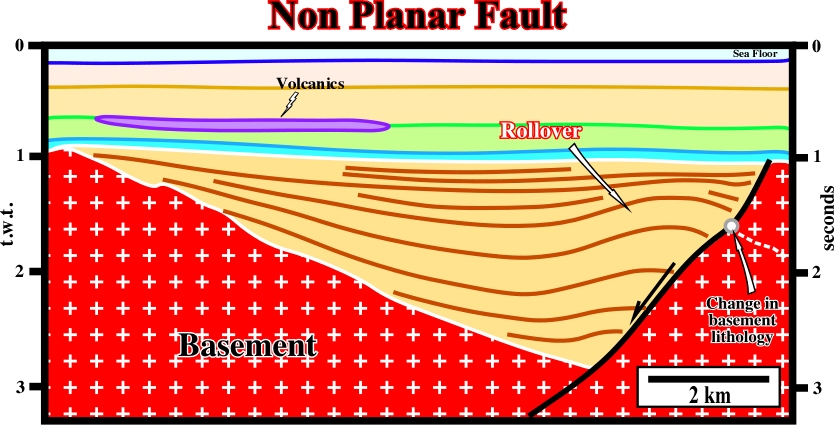

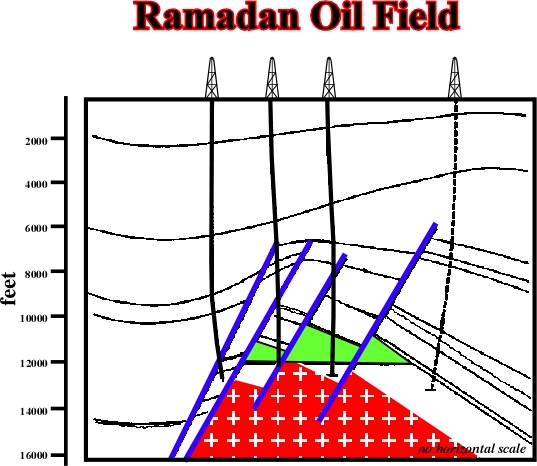

Fig. 189- The normal fault limiting this half-graben (rift-type basin) is no planar. The change of the dip of the fault plane is created by a lithological changing in the basement (Paleozoic rocks), Such a dip change created a volume problem in the half-graben and so the sediments were lengthened by a rollover structure, which indicates roughly the position of the lithological change (intersection of the axial plane of the rollover with the fault plane). Notice that on this seismic line the major fault is underlined by a more or less continuous reflector due to the great impedance contrast between the rift-type basin sediments and the basement |

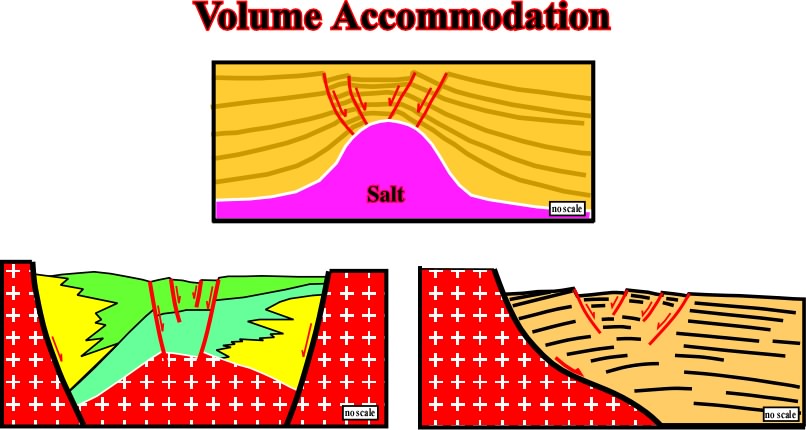

Fig. 190- In this figure are represented three typical examples of volume accommodation, in which the sediments were lengthened to fill the potential voids created by extension. Above, a salt diapir elongated the sediments in the top of the diapiric structure and so the sediments were lengthened by radial faults. Below, the right sketch illustrated, as the previous seismic line, how the geometry of ea fault limiting a rift-type basin can created a rollover, i.e. an antiform (extensional structure) with the associated stretching normal faults. Finally, the sketch on the left, is a typical example of the type-rift basins in onshore Sudan, where a Cretaceous extensional tectonic regime was followed by a Lower Tertiary extensional regime. The final result was the formation of half graben structures with opposed vergence which, when combined, give an apparent graben structure with a helical geometry, in which is almost impossible to find structural traps (four-way dips) associated with this kind of deformation. |

Fig. 191- In this tectonic regime, in which the sediments are lengthened, the chiefly extensional structures are graben or half-graben trending parallel to 2 and perpendicularly to the compressional structures of the foothills and fold belt associated (see fig. 74 and 75). |

|

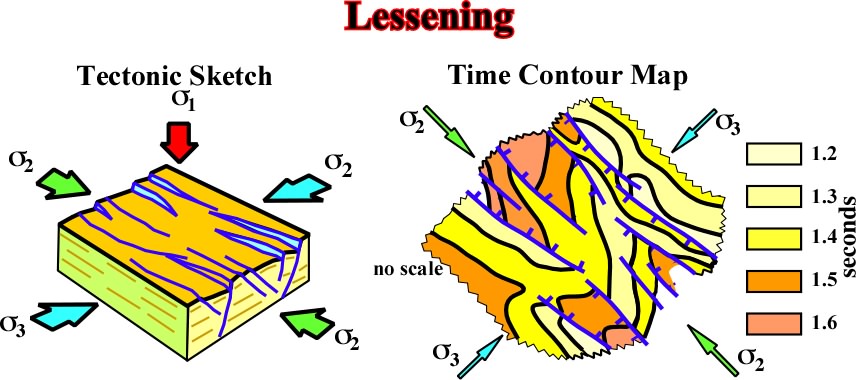

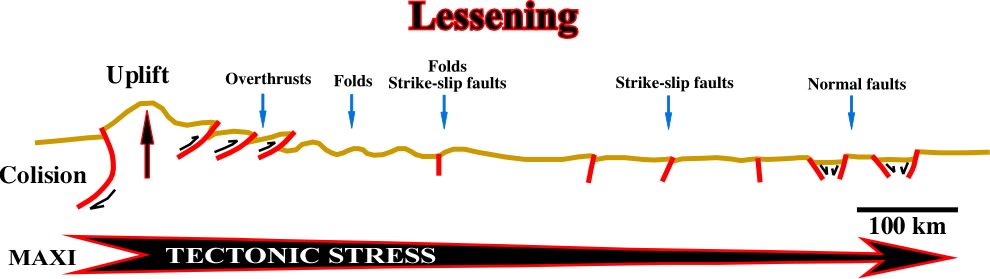

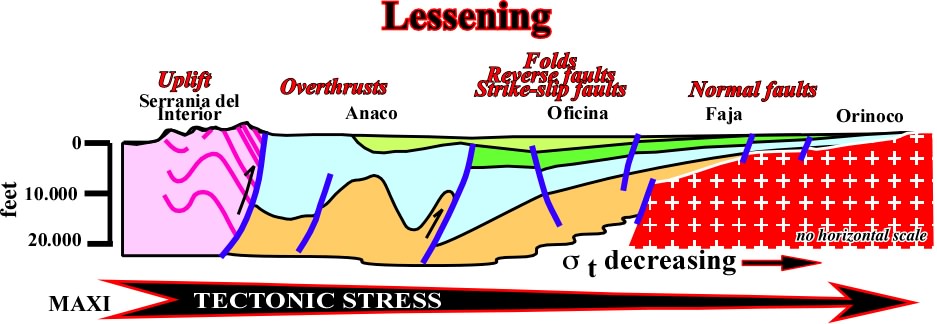

Fig. 192- Generally, this sequence of deformations (overthrusts -- folds -- strike-slip faults -- grabens) is interpreted as a result of relaxation of the tectonic stress (lessening of tectonic stress). Actually, as explained by J. Goguel, within a lithospheric plate, the tectonic stress is more or less constant. There is not lessening of the tectonic stress but just local changes in the sediments'' threshold deformation (rheological behavior) function of temperature and pressure |

Fig. 193- This geological cross section from Guyana shield to Serrania del Interior, in Venezuela, is illustrative of this sequence of deformations between the fold belt and the craton. As said previously (see fig. 74 and 75), in a certain area only the deformations of the adjacent tectonic regimes are possible (adjacent columns in Tectonic Regimes Table, fig. 74). So, three major areas can be considered in this cross-section. They are characterized by: (i) thrusts and cylindrical folds, (ii) Strike slip faults and conical folds and (iii) normal faults striking perpendicularly to the fold-belts. |

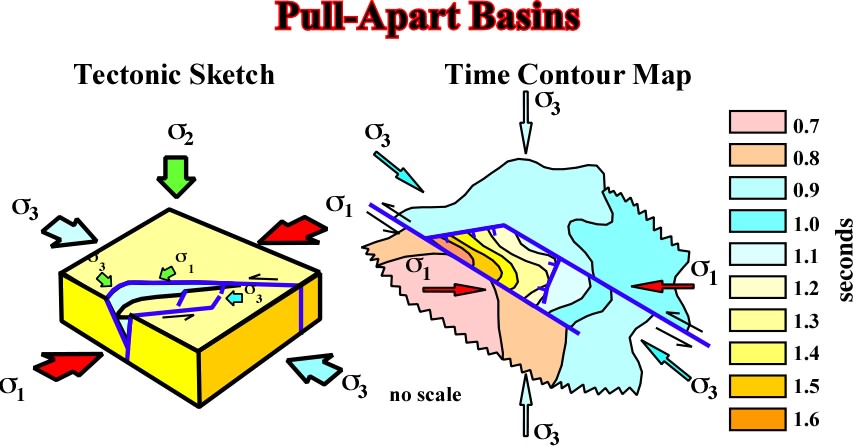

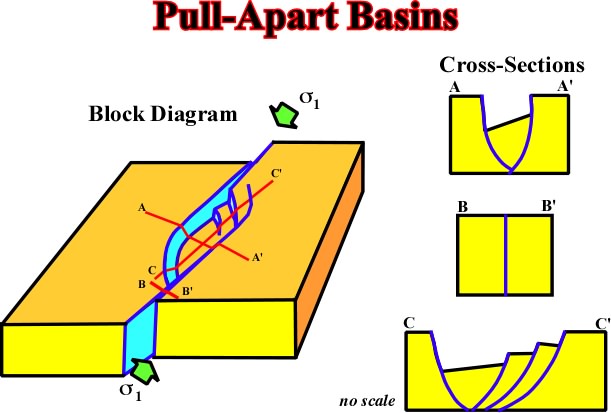

Fig. 194- Pull apart basin are developed in regional extensional tectonic regimes with s1 vertical. However, locally and in association with strike slip faults, local compressional tectonic regimes (with 2 vertical) can develop and create pull-apart basins, in which the seismic lines show completely different geometries as illustrted in fig. 195. |

|

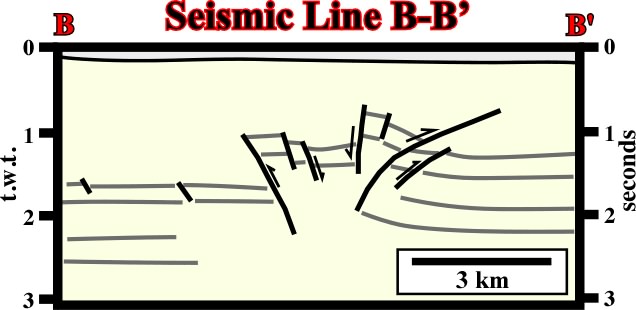

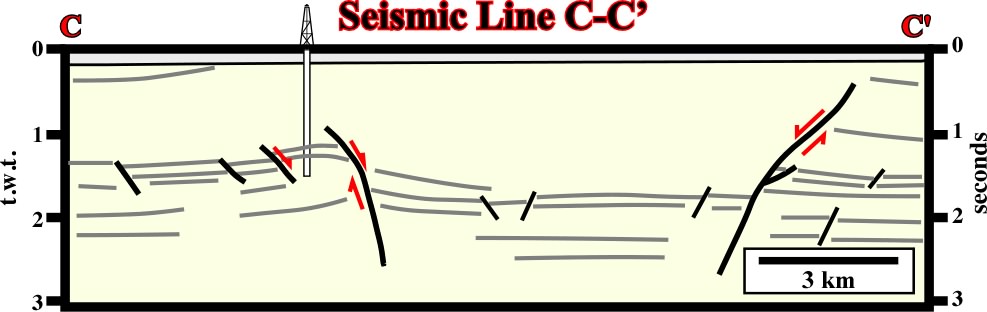

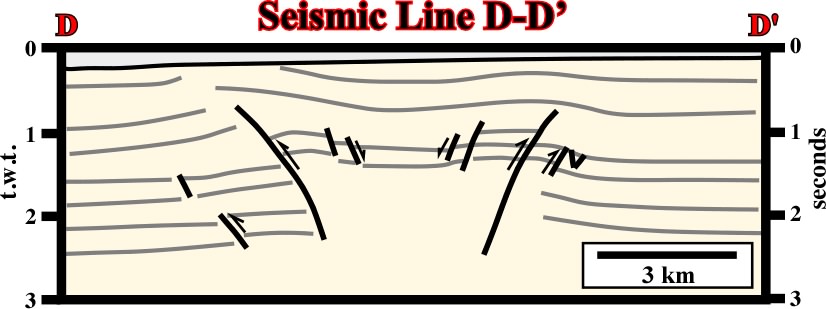

Fig. 195- On this sketch are represented three seismic lines illustrating different geometries found on pull-apart basins |

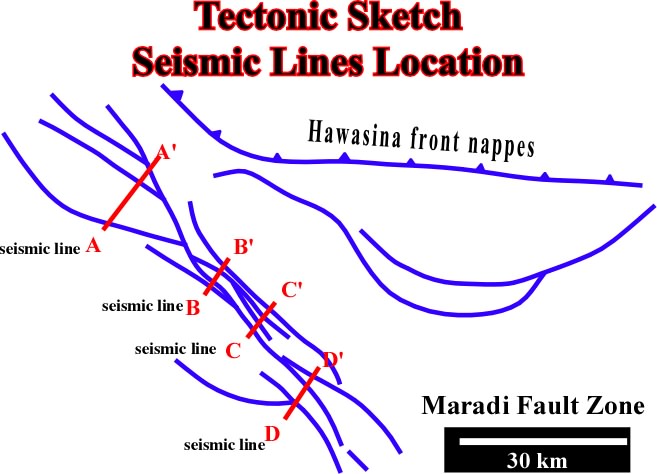

Fig. 196- Location of the seismic lines illustrated in the following figures |

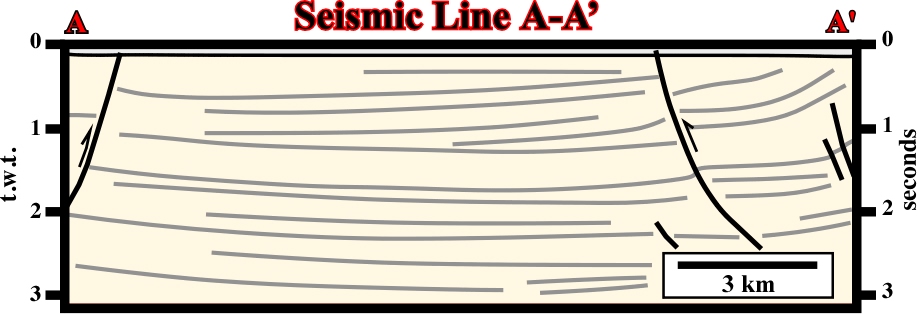

Fig. 197- On this seismic line the shortening is not quite quite evident, since the geometry of the faults seems normal, i.e. the inversions is relatively small |

|

Fig. 198- On this seismic line the shortening is evident. All faults have a reverse geometry, i.e. inversion and reactivation was strongly enough to change the fault geometry. |

Fig. 199- In spite of the fact thyat locally shortening is evident, one can say that on this line extension is preponderant. |

Fig. 200- Here again, inversion was strong enough and so the geometry of faults is predominantly reversal. |

|

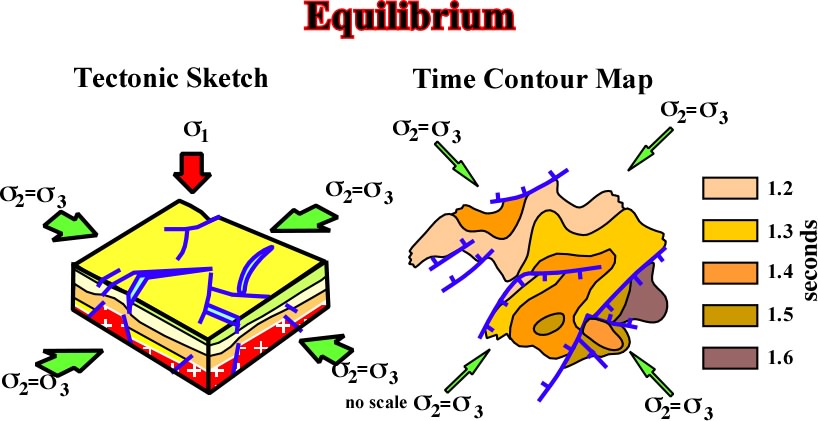

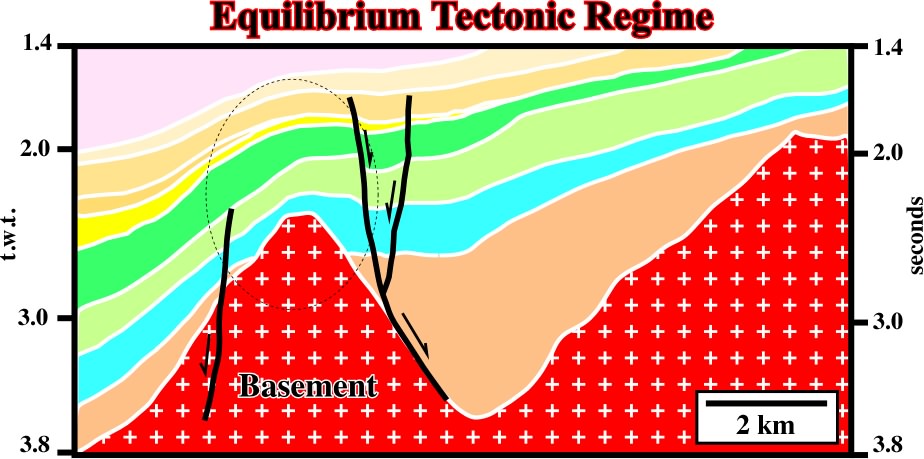

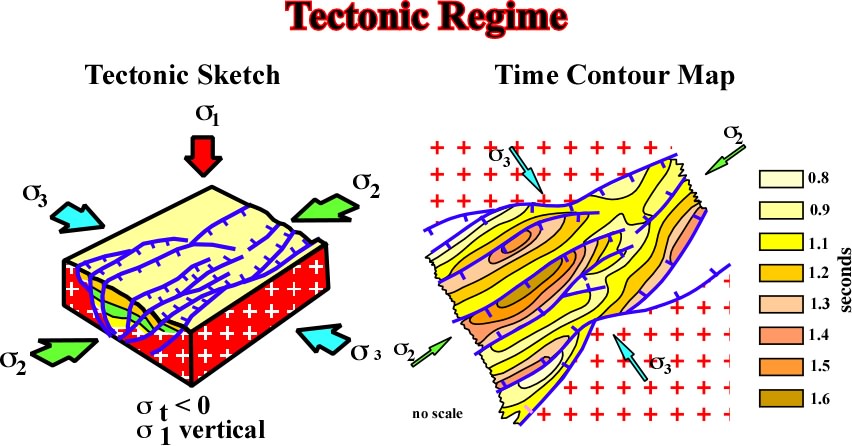

Fig. 201- Generally this tectonic regime, characterized by a 1 vertical and a 2 equal 3, that is to say by a biaxial ellipsoid is, is local. Indeed, it is often developed above diapiric structures (sal or shale domes) or buried hills. |

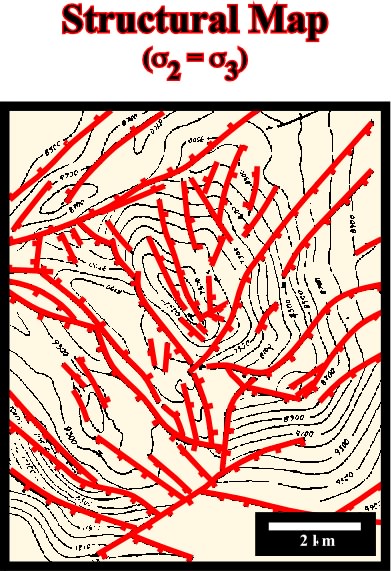

Fig.202- This tectonic regime (2 = 3 = confining stress) is rarely observed in field studies, However, it is often seen in geophysical maps that show random-oriented normal faults. In many cases, such a fault pattern reflects mainly a lack of tectonic analysis during the interpretation process than a tectonic regime with a tectonic stress nil. Nevertheless such a tectonic regime is found in association with halokinesis, shalokinesis and compaction structures over buried hills as it is probably the case in this structural map. |

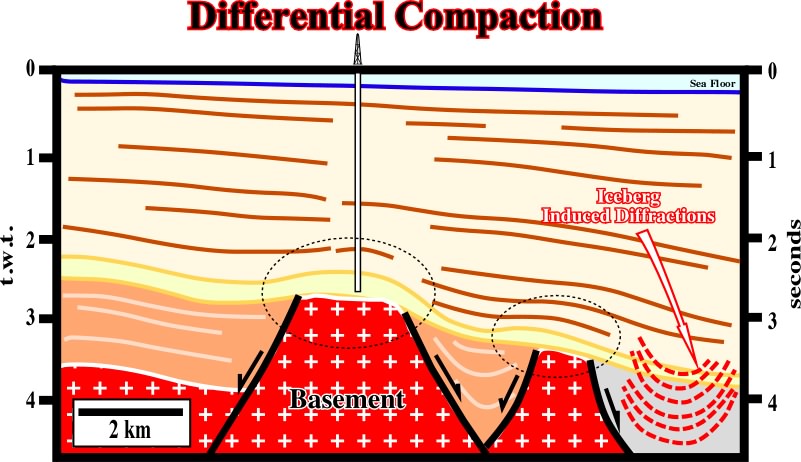

Fig. 203- On this seismic line, the structure tested by drilling correspond to a compaction structure over a high of basement (supracrustal rocks). The sediments of the cover were lengthened by more or less radial faults, which suggests a tectonic regime with a 2 equal to 3. On the right lower corner of the line, the moustaches correspond to the migration of the diffractions induced by an iceberg. The distance between the iceberg and the profile can be determined easily by a simple depth conversion |

|

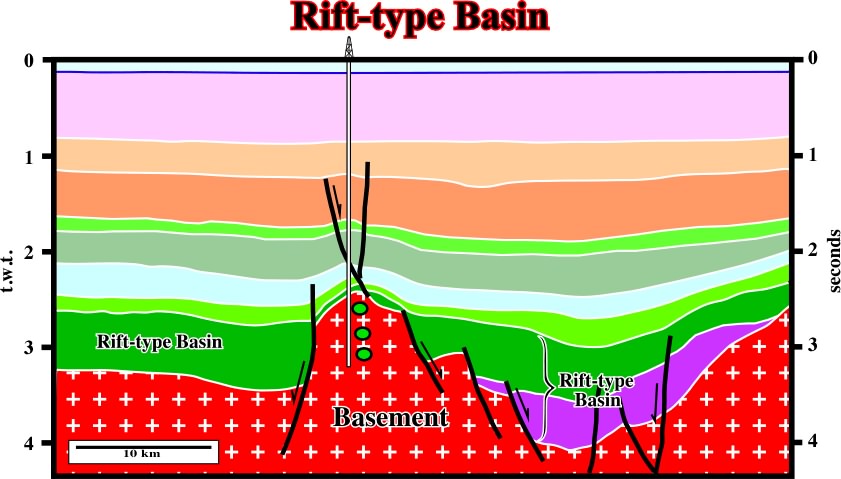

Fig. 204- A local equilibrium tectonic regime, characterized by a vertical s1 and a 2 equal to 3, is developed above the buried hills limiting the rift-type basins. In fact, the sediments overlying the buried hills were locally lengthened by more or less radial faults, whic are evident enough on the structural maps of the blue seismic interval. |

Negative Tectonic Stress Fig. 205- Sediments can only be lenthened by normal faulting. In addition, when the ellipsoid of effective stresses is triaxial the normal faults strike roughly parallel to the 2. |

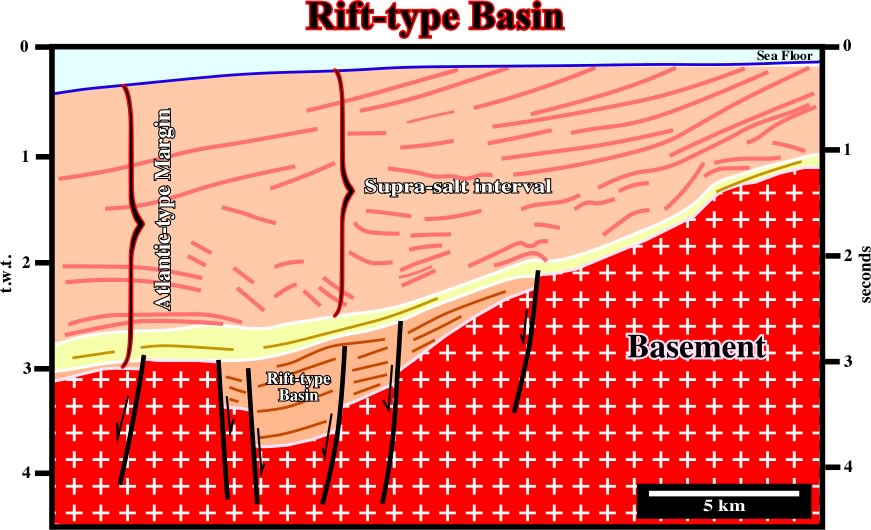

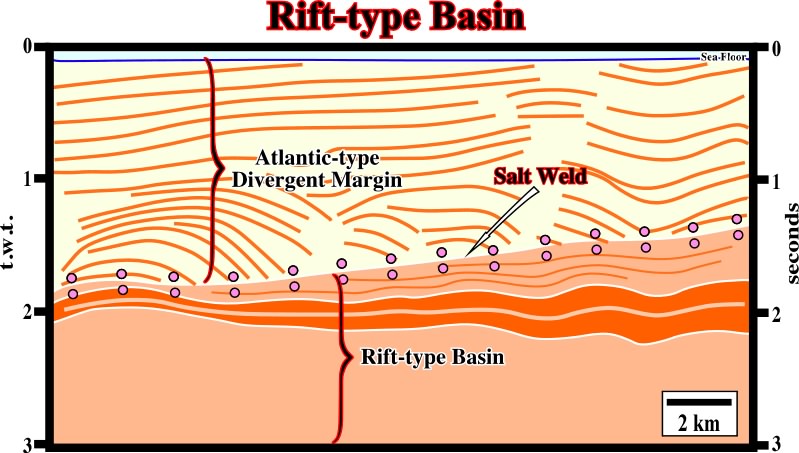

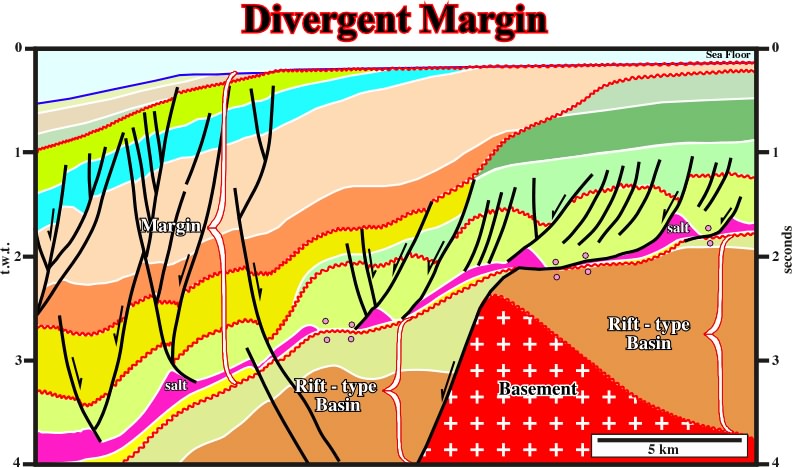

Fig. 206- A rift-type basin is clearly recognized within the basement and below the sediments of the the overlying divergent margin, in which a salt induced tectonic disharmony allows to differentiate supra and infrasalt sediments |

|

Fig. 207- When the rift-type basin are too big, their half-graben geometry is difficult to recognized as illustrated on this seismic line from offshore Cabinda (Angola). Indeed, below the salt induced tectonic disharmony, the rift-type sediments (the infrasalt sediments of the margin are under seismic resolution) look like those deposited in association with a regional subsidence rather than a differential subsidence. |

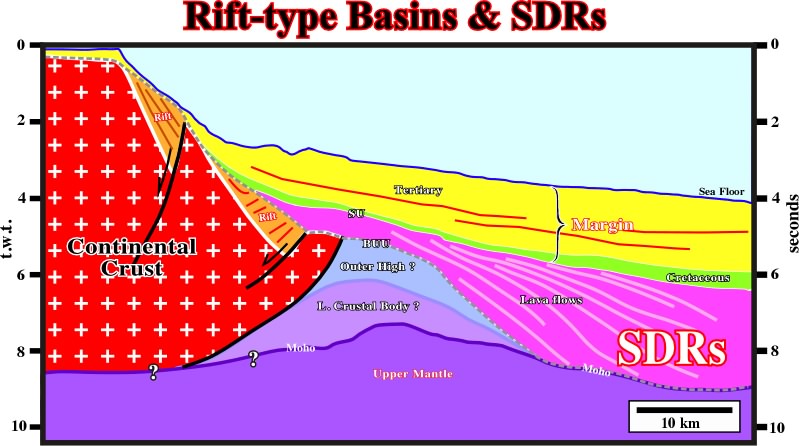

Fig. 208- Generally, the sediments of rift-type basins dip landward contrariwise to the post breakup subaerial lava flows which dip seaward (seaward dipping reflectors or SDRs). In this particular example, coming from offshore Brazil, it is quite easily to reconstruct the original dip of the rift-type sediments (before seaward tilting). In other words, explorationists should not confound the SDRs (without generating petroleum potential) with the sediments of the rift-type basins, which, under certain conditions, can be quite rich in organic matter and so considered as potential source rocks. |

Fig. 209- Structural high points in a rift are not the result of an uplift; they are the less subsident points. In other words, here is not development of horst structures but grabens (maximum of subsidence). |

|

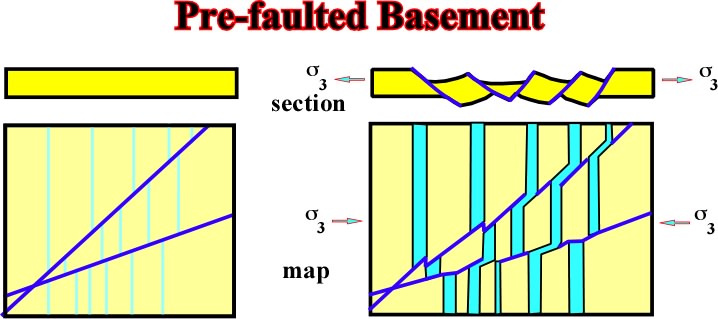

Fig. 210- When an heterogeneous basement is extended, normal faults parallel to 2 are formed. However, the pre-existent faults or weak zones can be reactivated creating open transfer basin oblique to 2 as shown above. |

Fig. 211- On this sketch, it is quite evident the dry wells were done before explorationists recognized where the reservoir interval was located. Indeed, when drilling morphological traps by juxtaposition (tilted blocks), the location of the well is dependent of the location of the potential reservoirs intervals. |

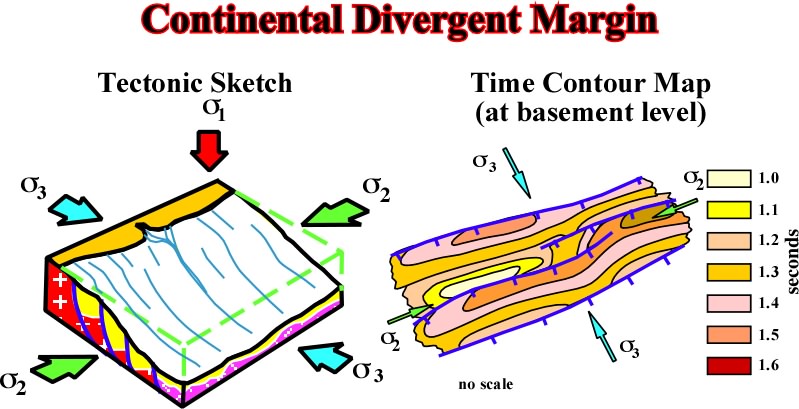

Fig. 212- Overlying rift-type basins, created by a differential subsidence, the margin is developed during a triaxial extensional tectonic regime, in which the 2 is roughly parallel to the shoreline. The space available for sedimentation is mainly created by thermal subsidence. Eustacy is responsible for the relative sea level changes and so the unconformities boundind the stratigraphic cycles |

|

Fig. 213- On this seismic line from the Offshore Angola, there are two major truncations near the outer shelf above the Atlantic Hinge Zone. Across this hinge zone, the base of salt (and base of Tertiary) has a cumulative vertical offset of about 3 s, equivalent to between 3 and 4 km. The deeper truncation is typically assigned to the middle to late Oligocene and is onlapped by Miocene strata. It was formed by up to 30 km landward erosion and 600 to 2000 m of vertical truncation of the Upper Cretaceous and Paleogene carbonate platform (Steckler et al., 1997, Congo; Karner et al. 1997, Gabon). The truncation coincides with a major eustatic fall in relative sea level of more than 300 m at about 30 Ma. But the estimated 2 km of truncation would requires that most of the relative fall in sea level was caused by epeirogenic uplift of the shelf. Note, that the thermal subsidence following continental breakup in the Neocomian would have been largely complete by the Oligocene. Thus, the Atlantic Hinge Zone owes very little to thermal subsidence, only a bit to eustatic changes, and much more to coastal uplift. The cause of this uplift may be connected with uplift above the Cameroon hotspot, which subsequently emplaced the Cameroon Volcanic Line in the Miocene (Meyers et al., 1996). Fluid inclusion temperatures in offshore Angola indicate a thermal pulse in the Miocene which raised temperatures by 30░ ¢ 40░C and the geotherm to 50¢60░C/km (Walgenwitz, 1990). Temperatures increased northward toward the Cameroon hotspot. Then followed a period of tectonic stability dominated by overall progradation as relative sea level rose to present-day levels. The shallower truncation affects the youngest strata on the outer shelf. The previous slide showed that across a width of at least 15 km on the shelf, Upper Cretaceous isopachous strata have been truncated at the sea floor. This line shows that farther west at the present shelf break, a zone at least 8 km wide contains Neogene foresets that end abruptly at the sea floor; their geometry suggests truncation rather than toplap. Truncation appears to be related to uplift and erosion of the entire Congo coastal plain, which created outcrop belts of successively older, truncated units in a landward direction. |

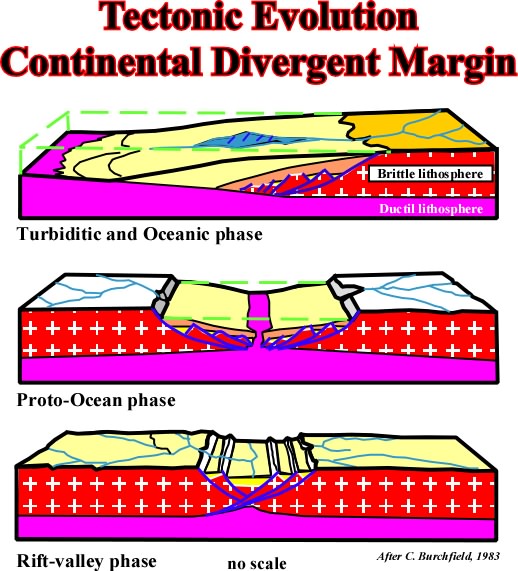

Fig. 214- This hypothesis was often refuted particularly in the timing of the breakup, which, as illustrated in the next figures, seems to take place at the end of the rifting phase and not during an hypothetical proto-ocean phase. |

Contents:

5.1- Basement Involved

5.1.2- Extension (1 vertical)

Generalities

a) Sequence of geological events

b) Dip of beds and dip of faults

c) Angle between the fault plane and the vertical

d) Depth of a detachment surface

e) Amount of extension

f) Ends of a normal fault

g) Normal faulting deformation

h) Intermediated fault blocks

i) No planar faults

j) Deformations in no planar faults

k) Associated grabens

5.1.2.1- Positive Tectonic Stress (t > 0)

a) Normal Faults - Grabens

b) Pull-apart Basins (Local stresses)

5.1.2.2- No Tectonic Stress (t = 0)

5.1.2.3- Negative Tectonic Stress (t <0)

a) Rift-type basins & Grabens

b) Continental margins divergent

c) Differential subsidence

d) Differential uplift

e) Transfer basins