| Mesozoic Paleogeography and Tectonic History, Western North America |

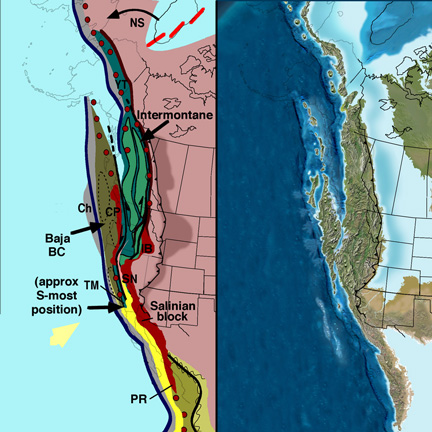

Baja BC and North America at 105 Ma |

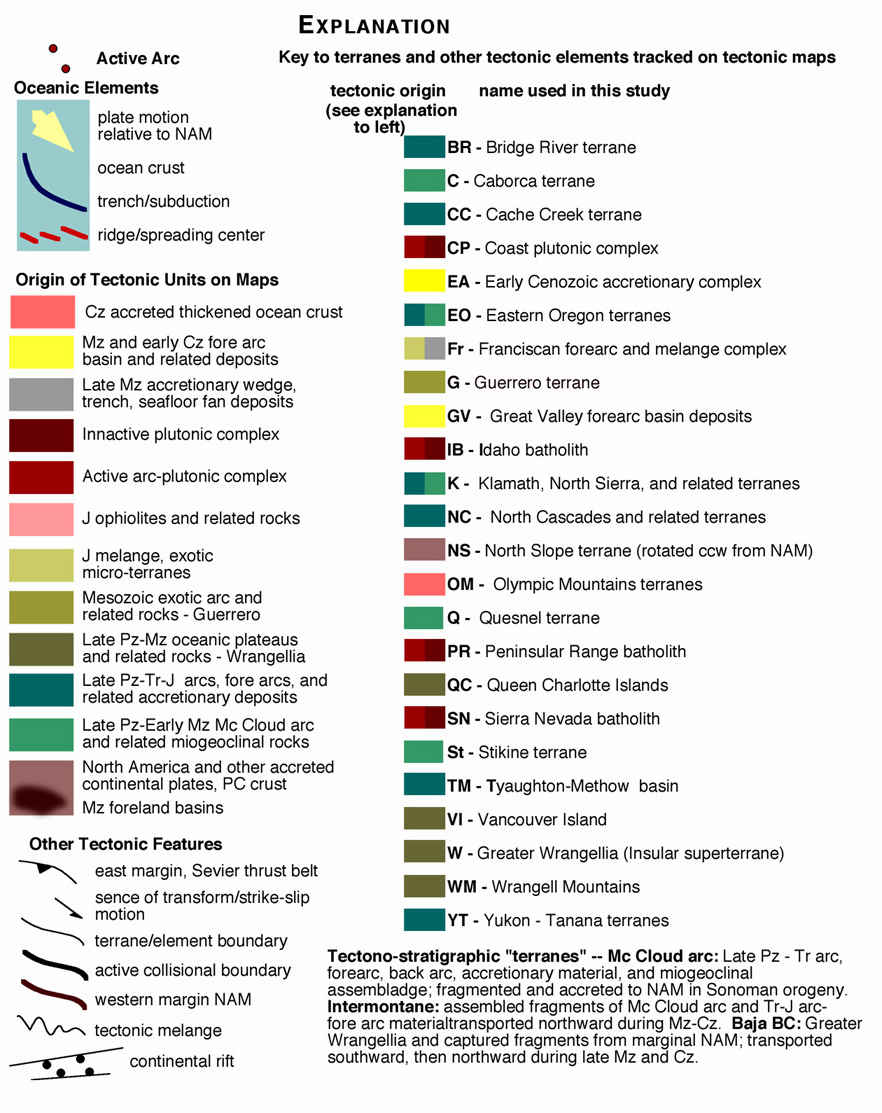

Legend |

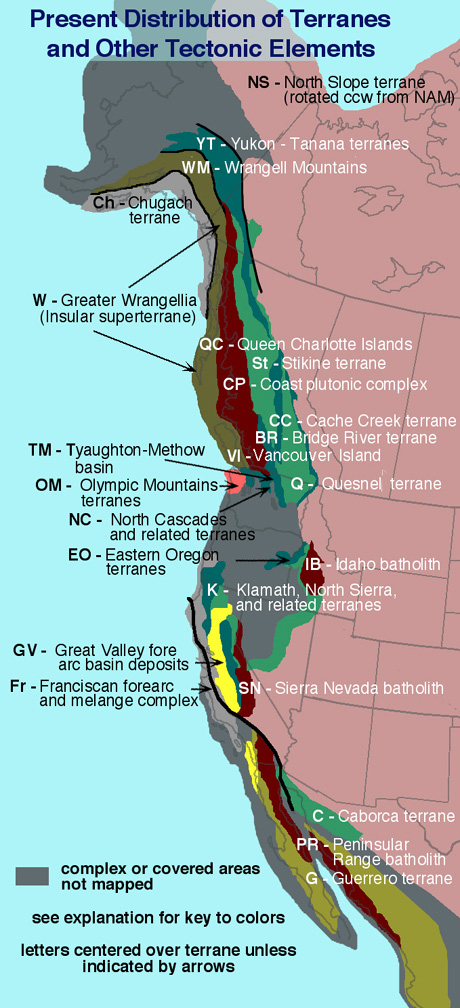

Present terranes |

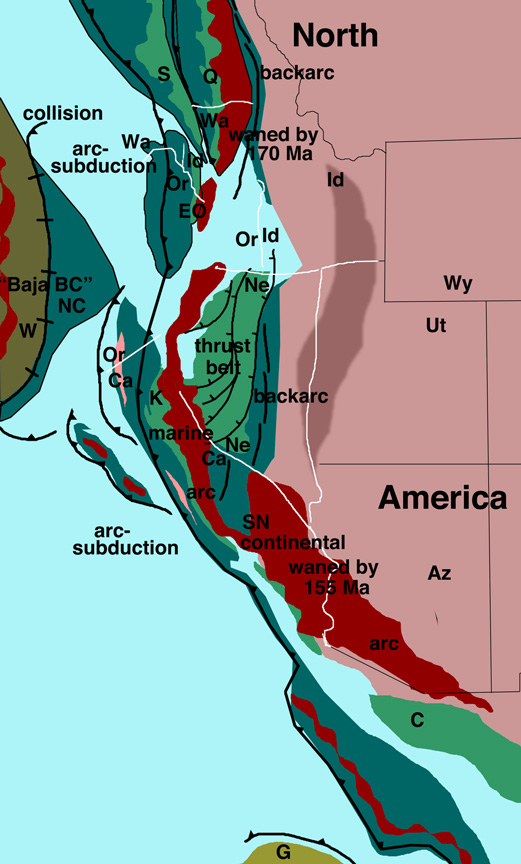

Map showing general Jurassic distribution of terranes (modified from Saleeby and Busby-Spera, 1992) |

from http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~rcb7/mz_paleogeog_wus.html

Images and text modified from a poster session presented to the Annual Meeting of the Geological Society of America, Seattle, Nov. 2003 by Ron Blakey and Paul Umhoefer, Department of Geology, NAU

Jurassic-Cretaceous Paleogeography, Terrane Accretion, and Tectonic Evolution of Western North America, Ronald C. Blakey and Paul J. Umhoefer, Department of Geology, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011

Key words: terrane accretion, tectonic evolution, western North America

Reconstruction of Mesozoic Cordilleran accretionary events can be partially constrained by a series of paleogeographic and tectonic maps at consecutive (15-20 m.y.) time intervals. Producing maps with temporal continuity results in a realistic sequence of tectonic events and plate motions, especially when constraining geologic and paleomagnetic data are included. Wrangellia and Guerrero (western Mexico) are considered exotic to North America. We trace the history of several basins and their relations to terranes and tectonic events including the Wrangell Mountains, Tyaughton-Methow, and Great Valley arc-related basins, and the Rocky Mountain foreland basin. The maps are based on a moderate view of terrane translation with respect to ''Baja BC''. We divide Jurassic-Cretaceous events into six time intervals. The following events are shown with moderately detailed paleogeography: 1) 180-160 Ma - major arc and oceanic terranes of diverse and controversial origin were accreted to western North America (eg. Quesnellia, Cache Creek, Stikine, related terranes of Klamaths and Sierra Nevada, southern Wrangellia?); 2) 160-145 Ma - major arc magmatism and sinistral oblique convergence with southerly displacement of outboard terranes; 3) 145-125 Ma - continued sinistral convergence and southward terrane displacement; Guerrero terrane approached Mexico; gaps in foreland basin; 4) 125-105 Ma - Guerrero arc accreted and new arc built on new western margin of Mexico; tectonic escape northward of several terranes; minor arc volcanism and major foreland subsidence; 5) 105-85 Ma - major outboard magmatism on Baja BC with an inner magmatic belt in hinterland of thrust belt; northern Wrangellia accretes and intervening basin closed; Kula-Farallon triple junction formed and Baja BC moved northward from latitude of present S. California; 6) 85-65 Ma - Strong oblique dextral convergence of Kula plate and northward translation of Baja BC; Laramide orogeny initiated along Farallon - North American plate boundary in S. California and NW Mexico; Rocky Mountain foreland basin remained active. When viewed as a whole, the proposed paleogeographic maps form a coherent picture of terrane accretion and dispersal dominated by oblique convergence. One anomaly is the accretion of southern Wrangellia 70 - 80 my before northern Wrangellia.

Syntheses of geologically complex regions over large amounts of time are challenging endeavors. Such studies must attempt to honor diverse geological and geophysical data and incorporate a wide range of complex and commonly differing interpretations of these data. In this study we present a regional synthesis of the tectonic assembly of Western North America from Permian to Early Tertiary, with emphasis on Jurassic and Cretaceous events. We attempt to track all major terranes and tectonic elements through a series of closely spaced paleotectonic and paleogeographic time slices. The time slices were originally assembled at 5-10 m. y. intervals and then presented at the intervals shown. By originally preparing such tight intervals, we were able to track individual elements within the constraints of available data and to check these events with respect to logical sequences of geologic events and plate-tectonic interactions at reasonable tectonic speeds.

When attempting this reconstruction, several major decisions must be made with respect to the origin of several important and controversial terranes and groups of terranes. We have followed a relatively conservative view concerning the origins of many of the terrane elements that comprise Western North America. Most terrane complexes have strong affinities to Western North America - from Permian through the Mesozoic, most were in proximity to the Cordilleran margin. The two major terranes that we acknowledge as exotic to North America are Greater Wrangellia (Insular Superterrane) and the Guerrero Superterrane. Many smaller terranes and blocks also suggest exotic origin but they were incorporated into larger elements with North American affinities. The Cordilleran margin was built during the late stages of the assembly of Pangaea and continued throughout the Mesozoic and Cenozoic. Our reconstructions show the following broad events: 1) After the Devonian-Mississippian Antler orogeny, the Mc Cloud arc was built on Western North America during the late Paleozoic. The Mc Cloud arc became dismembered and the various parts accreted to North America during the Triassic Sonoman orogeny. 2) During the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic, a series of fore arc and interarc elements formed west of and between elements of the dismembered Mc Cloud arc; some exotic material was incorporated into these terranes. The Cordilleran margin consisted of a southern continental arc and a northern marine arc. In some areas, the marine arc comprised two or more oceanic arcs. 3) In Middle and Late Jurassic, the exotic Wrangellia and Guerrero terranes approached the Cordilleran margin and the former collide with North America along its southern margin. The intervening Nutotzin Ocean closed from north to south and ophiolites accreted along the Cordilleran arc. As Wrangellia accreted, it was transposed southward along sinistral transform faults; parts of the northwest Cordilleran margin was captured by the south-moving block, the composite terrane referred to as Baja BC. 4) Baja BC moved southward during the Early Cretaceous and into the Late Cretaceous until about 100 Ma. The Nutotzin Ocean closed and a large transform separated Baja BC from the composite Intermontane terrane. 5) During Late Cretaceous and Early Tertiary, both Baja BC and Intermontane terranes continued northward dextral translation, though the former at a greater rate. By Late Eocene, both were in their approximate present latitude with respect to North America.

Paleogeography and Geologic History

Tectonic History Shown on Maps

Source