| South CAVA, South Nicaragua Volcanoes |

(a) Tectonic map of Central America. Major Plate boundaries are marked, as is the location of the Cocos aseismic ridge. Arrows show absolute plate motions (Morgan and Phipps Morgan, 2007) of the Cocos, North American, and Caribbean Plates in mm/yr. See text for further discussion. (b) Predicted Ў®idealЎЇ McKenzie and Morgan (1969) geometry for a stable CocosЁCCaribbeanЁCNorth American Triple Junction (TJ) if it behaved according to the kinematic rules proposed by McKenzie and Morgan (1969), in which case the Cocos Plate should tear at the TJ, and a stable rigid plate TJ should have a faultЁCfaultЁCtrench configuration. This behaviour is not seen, the actual faultЁCtrenchЁCtrench TJ geometry is sketched in panel (c). (c) Observed plate tectonic geometry near the CoЁCCarЁCNAm TJ. The Cocos Plate does not tear. Instead, differential NAmЁCCar plate motion is accommodated by arc compression N. of the CarЁCNAm transform fault (the MotaguaЁCPolochic shear zone), and by shear and extension south of the CarЁCNAm transform boundary. The forearc remains continuous across the location of the TJ, which implies that the Central American forearc arc-normal motions are coupled to the roll-back of the Cocos Plate (e.g. are more North American than Caribbean motion); while the relative lack of arc-perpendicular extensional structures within the Central American Forearc implies that it has at most a small SE-ward motion with respect to the forearc N. of the triple junction, so that its entire motion can be viewed as mostly Ў®North AmericanЎЇ. This implies that Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua should be regions of arc-normal extension between the NAm-like forearc and the Caribbean backarc. See text for further discussion. (d) Location of the Chiapas Massif batholith that is uncut by the Polochic Fault (Guzman-Speziale and Meneses-Rocha, 2000). Also shown are recent GPS velocity measurements with respect to the North American plate, using the CarЁCNAm solution of DeMets (2001). Vectors without uncertainty ellipses are from Lyon-Caen et al. (2007), who estimate their uncertainties to be about ЎА 2 mm/yr. Velocity vectors with uncertainties are from Turner et al. (2007). The three blue vectors are those used for the GPS estimate of the Caribbean plate motion east of the Nicaraguan arc in Fig. 3. The 5 purple vectors are those used for the GPS estimate of the Nicaraguan forearc motion west of the Nicaraguan arc in Fig. 3. (e) Blowup of the topography near the CocosЁCCaribbeanЁCNorth American Triple Junction. (Figure courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech). Note that the North AmericanЁCCaribbean transform boundary does not continue as a structural feature within the forearc.http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012821X08003191 |

(a) Regional Map of Central America and the Caribbean Plate. Across Central America, the CaribbeanЁCNorth American Plate boundary follows the MotaguaЁCPolochic fault system up to the axis of the arc; it does not have a structural continuation across the forearc (see blow-up of the topography in this region in Fig. 2e and further discussion of this point in Fig. 2dЁCe.). Deformation within Central America is strongly correlated with changes in the motion of the overriding plate relative to the subducting Cocos Plate. North of the CocosЁCCaribbeanЁCNorth American Triple Junction (located above the Ў®GЎЇ in Guatemala, see also Fig. 2a) the Ў®extraЎЇ westward component of North American plate motion relative to Caribbean plate motion correlates with compressive arc tectonics in Chiapas, Mexico. South of the Triple Junction, the extra Ў®eastwardЎЇ component of Caribbean plate motion relative to North American correlates with extensional and shear tectonics within the arc (In Guatemala, extension occurs in separate rift structures located behind the arc). The location of Fig. 3 is shown by the black box.http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012821X08003191 |

|

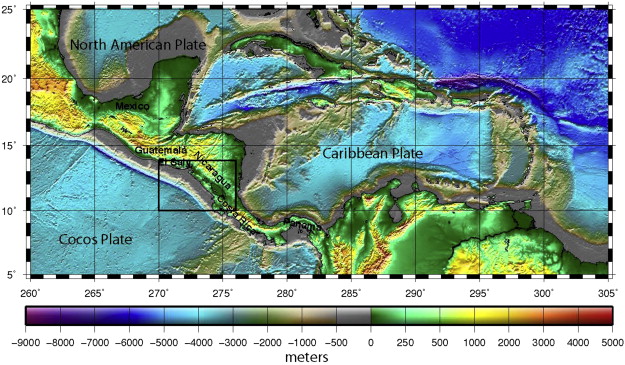

Shaded and colored SRTM elevation model of Central America (NASA/JPL/NGA, 2000) and high-resolution bathymetry along the Middle America Trench (MAT) from Ranero et al. [2005] including the working area and also the offshore sample locations. The line of Central American arc volcanoes runs through the two large lakes and parallel to the trench at about 200 km distance. Names of numbered volcanoes listed at lower left. Dots show core positions of RV METEOR cruises M66/3a+b, M54/2 and RV SONNE cruise SO173/3 along and across the trench - https://sfb574.geomar.de/study-area |

Blow-up of the tectonic structures and lava-ages within the Nicaraguan section of the Middle American arc. Note the arc-parallel tectonic structures bounding the Nicaraguan graben, and the symmetric older arc-lava ages on both sides of the active arc. Strike-slip bookshelf faulting in the graben (La Femina et al., 2002) possibly coexists with persistent arc-normal extension. Arrows show rates of North AmericanЁCCaribbean Plate motion (Demets, 2001 and this study) projected to arc-parallel shear and arc-normal extension in Nicaragua and El Salvador. Solely due to the change in strike of the arc, Nicaragua has a larger component of predicted extension that does El Salvador. If the Cocos Plate does not tear at the CocosЁCCaribbeanЁCNorth American TJ, then arc-perpendicular motion of the Central American forearc will be coupled to the roll-back of the Cocos Plate, in which case the forearc would be expected to retreat westward somewhat slower than the westward motion of the North American Plate. If the Cocos Plate smoothly deforms Ў®towardsЎЇ a Caribbean rate of rollback, then there would be a gradual southwards reduction in rollback. In this case, arc-normal extension would be reduced ЎЄ we think the reduction is from the ~ 15 mm/yr predicted for a rigid North American forearc moving at NUVEL1a velocity with respect to the Caribbean Plate to the ~ 6 mm/yr inferred from the ~ 100 km arc-normal separation between the 14ЁC18 Ma sections of the paleo-arc. Note that the two volcanic belts on either side of the graben would also have undergone ~ 100 km of arc-parallel shear, with the seaward 14ЁC18 Ma volcanic center having remained relatively stable with respect to the North American Plate, while the interior volcanic complexes translated towards the East as they remained relatively fixed with respect to the Caribbean plate. The purple and blue GPS vectors that suggest a modern arc-normal extension rate of ~ 3 mm/yr are based on the average velocities of the purple and blue velocity vectors shown in (Turner et al., 2007). They show Nicaraguan forearc (purple arrow) and backarc=Caribbean (blue arrow) velocities with respect to the North American Plate. Intra-arc extension in Central America: Links between plate motions, tectonics, volcanism, and geochemistry. This study revisits the kinematics and tectonics of Central America subduction, synthesizing observations of marine bathymetry, high-resolution land topography, current plate motions, and the recent seismotectonic and magmatic history in this region. The inferred tectonic history implies that the GuatemalaЁCEl Salvador and Nicaraguan segments of this volcanic arc have been a region of significant arc tectonic extension; extension arising from the interplay between subduction roll-back of the Cocos Plate and the 10ЁC15mm/yr slower westward drift of the Caribbean plate relative to the North American Plate. The ages of belts of magmatic rocks paralleling both sides of the current Nicaraguan arc are consistent with long-term arc-normal extension in Nicaragua at the rate of ~ 5ЁC10mm/yr, in agreement with rates predicted by plate kinematics. Significant arc-normal extension can Ў®hideЎЇ a very large intrusive arc-magma flux; we suggest that Nicaragua is, in fact, the most magmatically robust section of the Central American arc, and that the volume of intrusive volcanism here has been previously greatly underestimated. Yet, this flux is hidden by the persistent extension and sediment infill of the rifting basin in which the current arc sits. Observed geochemical differences between the Nicaraguan arc and its neighbors which suggest that Nicaragua has a higher rate of arc-magmatism are consistent with this interpretation. Smaller-amplitude, but similar systematic geochemical correlations between arc-chemistry and arc-extension in Guatemala show the same pattern as the even larger variations between the Nicaragua arc and its neighbors. Key words: Plate Tectonics; extension; magmatism; arc geochemistry - http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012821X08003191 |

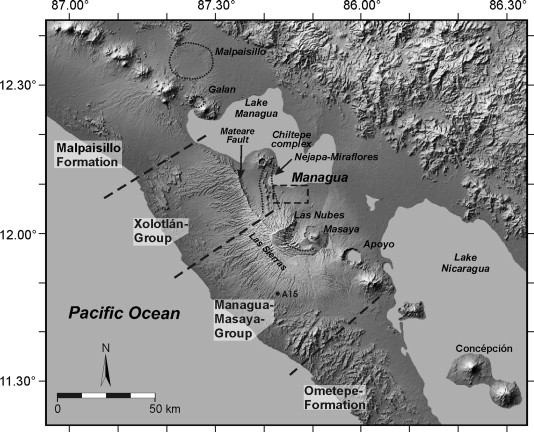

Map of western Nicaragua and the adjacent Pacific showing lakes Managua and Nicaragua within the NWЁCSE trending Nicaraguan depression and the arc volcanoes. Lines schematically indicate the areas between the volcanic front and the coast that are characterized by different tephrostratigraphic successions |

|

Sketch map of the sampled area around the Managua lake with location of samples, main tectonic lineaments (after van Wyk de Vries, 1993) and the volcanic centres: Adl (Asososca de Leon), Adm (Asososca de Managua), Ap (Apoyo), Aq (Apoyeque), Cn (CerroNegro), Eh (El Hoyo) Ji (Jiloa), Mg (Monte Galan), Mo (Momotombo), Ms (Masaya), Nj (Nejapa), NML (Nejapa-Miraflores Lineament), Rt (Rota), Tl (Telica), Ts (Tiscapa). In the inset on the left the regional tectonic setting of Nicaragua, with the active Central American volcanic chain. This paper reports new geochemical data on dissolved major and minor constituents in surface waters and ground waters collected in the Managua region (Nicaragua), and provides a preliminary characterization of the hydrogeochemical processes governing the natural water evolution in this area. The peculiar geological features of the study site, an active tectonic region (Nicaragua Depression) characterized by active volcanism and thermalism, combined with significant anthropogenic pressure, contribute to a complex evolution of water chemistry, which results from the simultaneous action of several geochemical processes such as evaporation, rock leaching, mixing with saline brines of natural or anthropogenic origin. The effect of active thermalism on both surface waters (e.g., saline volcanic lakes) and groundwaters, as a result of mixing with variable proportions of hyper-saline geothermal NaЁCCl brines (e.g., Momotombo geothermal plant), accounts for the high salinities and high concentrations of many environmentally-relevant trace elements (As, B, Fe and Mn) in the waters. At the same time the active extensional tectonics of the Managua area favour the interaction with acidic, reduced thermal fluids, followed by extensive leaching of the host rock and the groundwater release of toxic metals (e.g., Ni, Cu). The significant pollution in the area, deriving principally from urban and industrial waste-water, probably also contributes to the aquatic cycling of many trace elements, which attain concentrations above the WHO recommended limits for the elements Ni (∼40 μg/l) and Cu (∼10 μg/l) limiting the potential utilisation of Lake Xolotlan for nearby Managua.http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883292708000127 |

Lajas 923m, Holocene, shield volcano |

Las Lajas |

Las Lajas is the largest volcano of possible Quaternary age east of the Nicaraguan graben. The broad, low, basaltic shield volcano is truncated by a 7-km-wide, steep-walled caldera. The 650-m-deep caldera is breached by a narrow canyon on the SE side that drains into Lake Nicaragua. Five coalescing andesitic-dacitic lava domes are located in the center of the caldera, and additional domes are present on the outer flanks. Las Lajas was considered to be of Holocene age on the basis of youthful morphology (McBirney and Williams, 1965), however Plank et al. (2002) obtained three radiometric dates of Miocene age, and the main edifice may be older than previously thought. Van Wyk de Vries (1999, pers. comm.) earlier noted that Las Lajas itself was of probable Pleistocene age, but that youthful cinder cones on the flanks are similar to those of the Nejapa alignment and may be of Holocene age. Las Lajas volcano rises on the horizon NE of the flat-lying floor of the Nicaraguan central depression. The massive basaltic shield volcano is the largest Quaternary volcano east of the depression and contains a 7-km-wide caldera Photo by Benjamin van Wyk de Vries (Open University). http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-133&volpage=photos |

The SE side of the caldera of Las Lajas volcano is breached by a narrow canyon through which the Quebrada Las Lajas drains into Lake Nicaragua. The caldera walls of Las Lajas are up to 650 m high.Photo by Benjamin van Wyk de Vries (Open University).http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-133&volpage=photos |

The rounded lava dome in the center of the photo is a dacitic post-caldera dome that was constructed on the southern flank of the basaltic Las Lajas shield volcano. In addition to flank domes, five coalescing domes were constructed within the caldera.Photo by Benjamin van Wyk de Vries (Open University).http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-133&volpage=photos |

Apoyeque |

Two lake-filled calderas dominate the 11-km-wide Chiltepe Peninsula extending NE-ward into Lake Managua. Greenish Lake Apoyeque was the source of two major late-Pleistocene plinian pumice deposits, and dark-blue Lake Jiloa (Xiloa) produced the Jiloa Pumice about 6500 years ago. The two calderas cut the summit of the Chiltepe pyroclastic shield volcano. Nicaragua''s capital city Managua, extending across much of the right side of the image, has been subjected to major tectonic earthquakes. NASA Space Shuttle image ISS004-E-5765, 2002 (http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov/).Apoyeque (Laguna Apoye), 518m, is a pyroclastic shield, located in the Chiltepe Peninsula Natural Reserve in Nicaragua. It has a 2.8-km wide, 400-m-deep, lake-filled caldera. It is part of the Chiltepe pyroclastic shield volcano, one of three ignimbrite shields on the Nicaraguan volcanic front.The lake at its center, Apoyeque lake its shore 100 meters below the peak of the caldera, at its bottom reaches down to sea level. Immediately Southeast of Apoyeque peak is the 2.5 x 3 kilometer wide lake-filled Xiloa (Jiloa) maar, a part of the Apoyeque complex.Apoyeque, with a volcanic explosivity index (VEI) of 6, the second highest, had one of the largest explosions known in history, last erupted in about 50 BC.In addition to the Chiltepe dome (volc§Тn Chiltepe), which is used synonymously with Apoyeque, the Apoyeque complex contains the Jiloa caldera (Laguna de Jiloa aka Xiloa), the Miraflores dome and the Cerro Talpetate dome. An eruption of Laguna Xiloa 6100 years ago produced pumiceous pyroclastic flows that overlay similar deposits of similar age from Masaya. The Apoyeque volcanic complex occupies the broad Chiltepe Peninsula, which extends into south-central Lake Managua. The peninsula is part of the Chiltepe pyroclastic shield volcano, one of three large ignimbrite shields on the Nicaraguan volcanic front. A 2.8-km wide, 400-m-deep, lake-filled caldera whose floor lies near sea level truncates the low Apoyeque volcano, which rises only about 500 m above the lake shore. The caldera was the source of a thick mantle of dacitic pumice that blankets the surrounding area. The 2.5 x 3 km wide lake-filled XiloЁў (JiloЁў) maar, is located immediately SE of Apoyeque. The Talpetatl lava dome was constructed between Laguna Xiloa and Lake Managua. Pumiceous pyroclastic flows from Laguna XiloЁў were erupted about 6100 years ago and overlie deposits of comparable age from the Masaya plinian eruption. Apoyeque stratovolcano forms the large Chiltepe Peninsula in central Lake Managua. A 2.8-km wide, 500-m-deep caldera truncates the volcano''s summit, below and to the left of the airplane wing. Laguna de Jiloa, the large lake in the foreground, lies immediately SE of Apoyeque. The age of the latest eruption of Apoyeque is not known, but human footprints underlie pumice deposits thought to originate from Apoyeque volcano or a nearby vent beneath Lake Managua. Momotombo volcano is visible in the distance to the NW across Lake Managua. Last eruption 50 BC +/-1000 years - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apoyeque |

The Chiltepe Peninsula is seen across Lake Managua from the south on the outskirts of the city of Managua. The broad peninsula extends into the lake about 6 km north of the city and lies at the northern end of a chain of pyroclastic cones and craters that extends into the city. The small conical peak on the far right horizon is Volcan Chiltepe.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution).http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-091&volpage=photos Apoyeque pyroclastic shield volcano is located on Chiltepe Peninsula, in western Nicaragua. The volcano contains two calderas, and active fumaroles in Laguna Jiloa, and north caldera rim.Apoyeque Caldera -The steep-walled (2.8 km wide, 400 m deep) caldera contains a lake. The caldera is situated at the centre of Chiltepe Peninsula. The caldera rim and southern flanks are covered with a few metres deep layer of white pumice. In the east and north, the pumice is covered with several metres of white tuff.Jiloa (Xiloa) Caldera The caldera is located on the eastern flank of Chiltepe Peninsula. Laguna Jiloa occupies the caldera, which has been described as a low-rimmed explosion pit. The outer flanks of the caldera are covered with a 2 m deep layer of pumice, overlaid with white tuff. Volcan Chiltepe 228 m high (170 m above lake) high dome is located on the shore of Lake Managua, on the eastern side of Chiltepe Peninsula.Miraflores -this dome (180 m) is located 600 m SSW of Laguna Jiloa. Satellite photos show a recent-looking 200 m long landslide on NNE flank. Apoyeque Volcano Eruptions 50 BC Apoyeque, 1050 BC- Los Cedros Tephra, 2550 BC +/- 1000 West Chiltepe Peninsula, 4160 BC Laguna Jiloa (Xiloa) http://www.volcanolive.com/nicaragua.html |

The broad Chiltepe Peninsula rises to the SE across the flood-stained waters of Lake Managua. Apoyeque caldera lies beyond its horizontal rim on the right-center horizon. The 11-km-wide peninsula extends into Lake Managua and marks the northern limit of a segment of the central Nicaraguan volcanic chain that is offset to the east.Photo by Lee Siebert, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution). http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-091&volpage=photos |

The deep blue Laguna de Jiloa (left) and the turquoise-colored Laguna Apoyeque dramatically fill two calderas on the Chiltepe Peninsula north of Managua. The 2.8-km-wide Apoyeque caldera, the source of the major Chiltepe Pumice about 2000 years ago, has a more circular outline than the scalloped 2.5 x 3 km wide Jiloa caldera, which was the site of a major explosive eruption about 6500 years ago.Laguna de Jiloa was the source of a major explosive eruption about 6500 years ago that deposited the widespread Jiloa Pumice, which blankets the Managua area. Laguna de Jiloa (also spelled Xiloa) is seen here in an aerial view from the north with Lake Managua at the upper left. The rim of the 2.5-km-wide caldera is lowest on the SE (left) and rises to 220 m on the NW side. Cones of the Nejapa-Miraflores alignment can be seen extending to the south from the center of the far caldera rim. Photo by Jaime Incer, 1980. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-091&volpage=photos |

The forested Apoyeque stratovolcano is truncated by a 2.8-km-wide lake-filled caldera. Another lake-filled caldera, Laguna de Jiloa, is located immediately to the SE. The summit caldera of Apoyeque volcano is filled by a scenic lake. The age of the latest eruption of Apoyeque is not known, but human footprints underlie pumice deposits thought to originate from Apoyeque volcano or a nearby vent beneath Lake Managua. This view is from the west caldera rim with the Chiltepe Hills in the background. Photo by Alain Creusset-Eon, 1970 (courtesy of Jaime Incer.Laguna de Apoyeque fills a 2.8-km-wide caldera constructed at the center of the Chiltepe Peninsula. The caldera rim rises about 400 m above the lake, whose surface lies only about 40 m above sea level. Two major pumice deposits erupted about 18,000-25,000 years ago originated from Apoyeque caldera. The Lower Apoyeque pumice was erupted about 22,000-25,000 years ago, while the Upper Apoyeque pumice, which forms a distinctive layer in the Managua area, was erupted a few thousand years later. Lake Managua lies at the upper right. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-091&volpage=photos |

An archaeological site at Acahualinca near Managua exposes human footprints that were covered by voluminous pumice-fall deposits from Apoyeque volcano. The footprints are older than the overlying ca. 6500 yrs Before Present (BP) Jiloa Pumice and may occur within a ca. 7500 yrs BP mudflow deposit from Masaya volcano and thus range between about 6500 and 7500 yrs BP. These renowned footprints are the oldest indication of human habitation in the Managua area.Photo by Jaime Incer. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-091&volpage=photos |

|

Nejape-Miraflores, 12.12 N, 86.32 W, summit elevation 360 m, Fissure vents , Laguna crater Tiscapa crater is located a few km east of Managua city. Eruptions in the past 2500 years. |

Laguna de Nejapa (right center) and Cerro Motastepe (left-center horizon) are part of the N-S-trending Nejapa-Miraflores alignment. A series of pit craters and fissure vents extends into Lake Managua (barely visible at the far upper right) and is continuous with the volcanic vents on the Chiltepe Peninsula (far right horizon). The Nejapa-Miraflores alignment (also known as Nejapa-Ticoma) has been the site of about 40 eruptions during the past 30,000 years, the most recent of which (from Cerro Motastepe) occurred less than 2500 years ago. The N-S-trending Nejapa-Miraflores alignment, 360m, located near the western margin of the Nicaraguan graben, cuts through the western part of Nicaragua''s capital city, Managua. This alignment, which has erupted tholeiitic basaltic rocks similar to those from mid-ocean ridges, marks the right-lateral offset of the Nicaraguan volcanic chain. A series of pit craters and fissure vents extends into Lake Managua and is continuous with the volcanic vents on the Chiltepe peninsula. An area of maars and tuff cones perpendicular to the N-S trend of the lineament forms the scalloped shoreline of Lake Managua. Laguna Tiscapa crater is located several kilometers to the east near the central part of the city of Managua. The elongated Nejapa and Ticoma pit craters are surrounded by small basaltic cinder cones and tuff cones. The Nejapa-Miraflores alignment (also known as Nejapa-Ticoma) has been the site of about 40 eruptions during the past 30,000 years, the most recent of which (from Asososca maar) occurred about 1250 years ago.Eruption 1060+/-100 years. Photo by Jaime Incer. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-092&volpage=photos |

Cerro Motastepe cinder cone (upper left) is the youngest and most prominent feature of the Nejapa-Miraflores volcanic alignment. The cone, seen here from the SE with Laguna de Nejapa in the center of the photo, is elongated in an E-W direction and rises 160 m above its base to 360 m elevation. Cerro Motastepe formed less than 2500 years ago. The surface of saline Laguna de Nejapa collapse pit (center) lies at about the same level as Lake Managua, barely visible in the distance at the upper right. |

Laguna de Tiscapa partially fills a 700-m-wide maar is seen here from the SW with a skyscraper of downtown Managua in the right background. The 700-m-wide maar overlooks the central part of the city. Laguna de Tiscapa lies about 5 km east of the Nejapa-Miraflores crater lineament along a major fault that cuts through the city of Managua.The maar was constructed along a major fault that cuts through Managua. The crater overlooks the center of Managua and lies 5 km east of the N-S-trending Nejapa-Miraflores lineament, a 17-km-long chain of collapse pits and cinder-spatter cones that marks a point of right-lateral offset of the Nicaraguan volcanic chain.Photo by Jaime Incer. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-092&volpage=photos |

The steep-walled crater Laguna de Asososca provides water for the adjacent capital city of Managua. The elongated 1.3 x 1 km wide lake lies north of Laguna de Nejapa along the Nejapa-Miraflores lineament and is viewed here from the SE. In the background, beyond a bay of Lake Managua (the light-colored body of water at the upper right-center), is the Chiltepe Peninsula. This Laguna de Asososca is not to be confused with another crater lake of the same name at the southern end of the N-S-trending Las Pilas volcanic complex.Photo by Jaime Incer.http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-092&volpage=photos |

The N-S-trending Nejapa-Miraflores alignment of cones cuts across the western outskirts of the city of Managua and extends across a bay of Lake Managua onto the Chiltepe Peninsula. Cerro San Carlos (center) lies along the southern side of the bay, while the conical peak of Volcбn Chiltepe is visible at the upper left on the eastern tip of the Chiltepe Peninsula.Photo by Paul Kimberly, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution). http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-092&volpage=photos |

Cerro Motastepe cinder cone (upper left) is the youngest and most prominent feature of the Nejapa-Miraflores volcanic alignment. The cone, seen here from the SE with Laguna de Nejapa in the center of the photo, is elongated in an E-W direction and rises 160 m above its base to 360 m elevation. Cerro Motastepe formed less than 2500 years ago. The surface of saline Laguna de Nejapa collapse pit (center) lies at about the same level as Lake Managua, barely visible in the distance at the upper right. Photo by Lee Siebert, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution). http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-092&volpage=photos |

Geology of Asososca area following Pardo et al. (2008) including the geological map, cross-sections, and the general stratigraphic column. In the latter, black boxes indicate mafic compositions (basaltic to basalticЁCandesites); white boxes correspond to felsic units (rhyodacitic to dacitic), and gray-yellowish boxes are buried paleosols where radiocarbon data is available.http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027309001759 |

ASOT-A wet surge deposits. In proximal outcrops it begins with a basal, massive, altered bed followed by thin, discontinuous green, gray and yellow beds (A), where soft-sediment deformation (BЁCE, shown by arrows), fine lamination (FL), and accretional lapilli (AcL) are common. A corresponds to an outcrop inside the crater, B and E are outcrops close to Motastepe scoria cone, while C and D are outcrops located S to SE Asososca. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027309001759 |

A. Automatically detected lineaments in the NMVF. Results from the analysis of each Ў°pseudo-shadowЎ± image were merged in a single dataset, for polymodal Gaussian fitting and cumulative representation on a rendering of the DEM. Image processing for lineament enhancing includes the following steps: preparation of 9 directional-derivative filtered images (Ў°pseudo-shadowЎ± images); Laplacian filtering, threshold slicing, edge continuity enhancement and LIFE filtering (a specific filter to eliminate randomly scattered pixels) of each image. Eventually, the prepared images were processed by SID software for automatic lineament detection. B. Four lineament domains were found in the investigated area: a dominant N13ЎгW domain followed by N17ЎгE to N68ЎгE and N48ЎгW minor domains. Total data: 147, max: 7, min: 0, mean: − 4.940, standard deviation: 3.793, mode: − 12. RMS = 0.1694001. Best fit value = 0.2799953. C. Lineament density map zoomed in D, where a significant density is located in the western outskirts of Managua. E. Vent density map, zoomed in F. Identification of the aligned and often clustered eruptive vents (including tuff rings, maars, and scoria cones) was visually based on the assumption that volcanic features, in absence of external influence, are characterized by circular morphology both in cases of constructive activity and of destructive activity (Lesti et al., 2008). A subset of the panchromatic band 8 (0.52ЁC0.9 mm) of the Landsat scene (path: 017; row: 052; acquisition date: 5/11/1999) was processed by highpass spatial filter (3 Ч 3 kernel size) to emphasize the morphological contrast. As many as 50 vents were detected by visual inspection (Goward et al., 2001) both in the enhanced satellite image and in the Ў°pseudo-shadowЎ± DEM image of the investigated area. The density map derived from the spatial distribution of the identified vents (by the Interpreter Module in Erdas Imagine 9.0) shows a dominant NЁCS alignment that correlate with the location and direction of the highest lineament density area.http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027309001759 |

Volcanes Momotombo Y Momotombito, Lago de Managua |

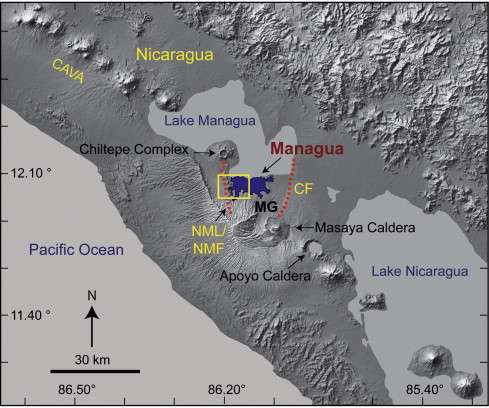

Map of western Nicaragua, showing the Central American Volcanic Arc (CAVA), the Pacific Ocean, lakes Nicaragua and Managua, Managua City, the NejapaЁCMiraflores Lineament and Fault (NML/NMF), the Cofradias Fault (CF) (dashed orange lines), the Managua Graben (MG), Chiltepe Volcanic Complex and Masaya and Apoyo calderas. Yellow box shows the study area in the NML Map of study area, showing western Managua, eruptive centers Asososca Maar (AM), Motastepe Scoria Cone (MSC), Hormigуn Scoria Cone (HSC), Ticomo Valley (TV) and Nejapa Maar (NM) http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027310000545 The 1245 yr BP Asososca maar: New advances on recent volcanic stratigraphy of Managua (Nicaragua) and hazard implications. Asososca maar is located at the western outskirts of Managua, Nicaragua, in the central part of the active, NЁCS trending and right-lateral NejapaЁCMiraflores fault that marks an offset of the Middle America Volcanic Arc. It constitutes one of the ∼ 21 vents aligned along the fault, between the Chiltepe Volcanic Complex to the North and Ticomo vents to the South. Asososca consists of an EastЁCWest elongated crater filled by a lake, which is currently used for supplying part of Managua with drinking water (10% of the capital city demand). The crater excavated the previous topography, allowing the observation of a detailed Holocene stratigraphic record that should be taken into account for future hazard analyses. We present a geological map together with the detailed stratigraphy exposed inside and around Asososca crater aided by radiocarbon dating of paleosols. The pre-existing volcanic sequence excavated by Asososca is younger than 12,730 + 255/− 250 yr BP and is capped by the phreatoЁCplinian Masaya Tuff (< 2000 yr BP). The pyroclastic deposits produced by Asososca maar (Asososca Tephra, in this work) display an asymmetric distribution around the crater and overlie the Masaya Tuff. The bulk of the Asososca Tephra is made of several bedsets consisting of massive to crudely stratified beds of blocks and lapilli at the base, and superimposed thinly stratified ash and lapilli beds with dune structures and impact sags. Coarser size-fractions (>− 2ϕ) are dominated by accidental clasts, including basaltic to basalticЁCandesitic, olivine-bearing scoriae lapilli, porphyritic and hypocrystalline andesite blocks and lapilli, altered pumice lapilli and ash, and ignimbrite fragments. Juvenile fragments were only identified in size-fractions smaller than − 1ϕ in proportions lower than 25%, and consist of black moss-like, fused-shape, and poorly vesiculated, fresh glass fragments of basaltic composition (SiO2 ∼ 48%). The Asososca Tephra is interpreted as due to the emplacement of several pyroclastic surges originated by phreatomagmatic eruptions from Asososca crater as suggested by impact sags geometry and dune-crest migration structures. According to radiocarbon dating, these deposits were emplaced at 1245 + 125/− 120 yr BP. The stratigraphic position of the Asososca Tephra and the well-preserved morphology of the crater indicate that Asososca is the youngest vent along the NejapaЁCMiraflores fault. Explosive eruptions might therefore occur again along this fault at the western outskirts of Managua. Such kind of activity, together with the strong seismicity associated to the active fault represents a serious hazard to urban infrastructure and a population of ca. 1.3 million inhabitants.Geological map of the southern and central segment of the Nejapa fault, comprising the volcanic centers of Ticomo, Nejapa, Motastepe, Embajada, Asososca, Satelite, Refineria, Los Arcos, Cuesta El Plomo and Acahualinca. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027308002138 |

Map of western Nicaragua, showing the Central American Volcanic Arc (CAVA), the Pacific Ocean, lakes Nicaragua and Managua, Managua City, the NejapaЁCMiraflores Lineament and Fault (NML/NMF), the Cofradias Fault (CF) (dashed orange lines), the Managua Graben (MG), Chiltepe Volcanic Complex and Masaya and Apoyo calderas. Yellow box shows the study area in the NML Map of study area, showing western Managua, eruptive centers Asososca Maar (AM), Motastepe Scoria Cone (MSC), Hormigón Scoria Cone (HSC), Ticomo Valley (TV) and Nejapa Maar (NM) http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027310000545Nejapa Tephra: The youngest (c. 1 ka BP) highly explosive hydroclastic eruption in western Managua (Nicaragua). Nejapa Maar (2.5 Ч 1.4 km, c. 120 m deep), the largest maar along the 15-km-long Holocene NejapaЁCMiraflores Lineament (NML), is the source vent of the youngest relatively widespread basaltic tholeiitic tephra blanket (Nejapa Tephra: NT) in western central Nicaragua, as shown by isopachs and isopleths (Rausch and Schmincke, 2008). The NT covers an area of > 10 km2 in W/NW Managua. The minimum total magma volume erupted is estimated as 0.09 km3. Juvenile, dominantly slightly vesicular (20ЁC40 vol.%) basically tachylitic cauliflower-shaped lapilli with an average density of 2.1 g/cm3, make up > 90 vol.% of the deposit, while lithoclasts comprise < 10 vol.% except proximally. This, the paucity of fine-grained tuffs and the dominant plane-parallel bedding all suggest fragmentation by shallow interaction of a rising magma starting to vesiculate and fragment pyroclastically with external water. The complex particles so generated erupted in moderately high eruption columns (at least 7ЁC10 km) and were dominantly deposited as dry to damp, warm to cool fallout. Minor surge transport is inferred from fine-grained, locally cross-bedded tephra beds chiefly north of Nejapa and just west of Asososca Maars. Synvolcanic faulting along the NML is inferred. Faults in the study area indicate that activation of the NЁCS-trending NejapaЁCMiraflores Fault (NMF), representing the western flank of Managua Graben, preceded deposition of NT and underlying Masaya Tuff (c.1.8 ka BP), Chiltepe Pumice (c. 1.9 ka BP) and Masaya Triple Layer (2.1 ka BP). The NT deposit is underlain regionally by a paleosol and topped by a soil. The basal paleosol contains pottery sherds made by the Usulutбn negative technique during the Late Formative period (700 BCEЁC300 CE) (2.7ЁC1.7 ka BP). The soil overlying NT contains pottery related to the Ometepe technique dated as between 1350 and 1550 CE (650ЁC450 a BP). These, and the radiocarbon dates of the pottery-bearing paleosols (1245 ЎА 125 and 535 ЎА 110 a BP) obtained by Pardo et al. (2008) indicate that Nejapa Maar erupted between c. 1.2 and 0.6 ka BP.Future eruptions in this area of similar magnitude, eruptive and transport mechanisms would represent a major hazard and risk to the densely populated western suburbs of Managua, a city expanding rapidly westward. Assuming a similar eruption scenario, poor-quality roofs, common in Nicaragua, would be prone to collapse up to 12 km peripheral to Nejapa Maar or another close-by eruptive site, and buildings at a distance of up to 500 m are likely to be severely affected. In view of the past frequency of eruptions along the NML, further eruptions are likely to occur in the near future. Key words: NejapaЁCMiraflores Lineament (NML);hydroclastic eruption; Nejapa Maar; Managua (Nicaragua) http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027310000545 |

Grayish, cauliflower-shaped lapilli-rich beds (> 90 vol.%) of the NT deposit. Inset: typical dense cauliflower-shaped lapillus of NT |

A) Stratigraphy of the study area in the new road to Leon: Asososca Tephra (AT), Scoria Cone Deposits I and II (SCD I + II), Masaya Triple Layer (MTL), Chiltepe Tephra (CT), Masaya Tuff (MT), Nejapa Tephra (NT) and local Post-NT Scoria deposit (PNTS) (yellow dashed lines). CT is difficult to recognize because it is very thin (∼ 10 cm). Inset map: location of the outcrop 002 ASO. (B) Grayish coarse- to medium-grained lithoclast-rich Asososca Tephra (AT). Angular basaltic blocks up to 30 cm large (arrows). Scale 2 m. (C) Detailed photograph showing Scoria Cone Deposits I and II (SCD I + II), Masaya Triple Layer (MTL), Chiltepe Tephra (CT), Masaya Tuff (MT) topped by Nejapa Tephra (NT). Scale 2 m http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027310000545. |

Stratigraphy of the southern lobe of NT, showing units IЁCV (yellow dashed lines). Scale 2 m. Inset map: location of the outcrop 006 NEJ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027310000545 |

Stratigraphy of western and northern lobes of NT. NT is subdivided into units I, II, III and IV separated from each other by the marker beds A, G and M. Inset map: location of the outcrop 008 MOT; (B) close-up of undulated base of NT, caused by closely spaced bushes draped by fine-grained basal layers. Note fan-like molds of small branches; and (C) close-up of marker bed G intercalated between units II and III http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027310000545 |

A. Older base surge deposits at Cuesta del Plomo outer crater rim. The great thickness and grain sizes involved, as well as the depositional structures such as impact sags and dunes, suggest a proximal vent. These deposits are part of the CPT unit, which underlies the Upper Apoyeque Tephra (UAq). B. The Refineria Tephra (RT) and the Satйlite Tephra (ST) crop out inside Asososca, at the northern crater wall. RT overlies a thick paleosol (Ps5) and is separated from ST by paleosol Ps6. Dry pyroclastic surges, ash fallout, and scoria fall deposits compose RT unit. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027308002138 |

The El Hormigon Tephra (HT), composed of scoria fallouts, is well exposed West of Asososca crater and characterized by blocks and bombs in a clast-supported, unsorted matrix. Clast-size and thickness suggest a proximal source likely located at the Hormigon quarry.http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027308002138 |

A, Showing the Northern Nejapa Tephra, El Hormigón Tephra, Motastepe Tephra, Masaya Triple Layer, Chiltepe Tephra, Masaya Tuff, and Asososca Tephra as exposed along the New Road to León. B, Motastepe scoria cone deposits overlain by the gray base-surge deposits of the Asososca Tephra, as exposed on Motastepe northwest quarried flank. C, Shows the planar, cross-bedding, and ballistic impact sags structures within the Asososca Tephra; the transport direction is from left to right, southwestward from Asososca Maar. Note the charcoal found at the base of the Asososca Tephra.The Nejapa Volcanic Field (NVF) is located on the western outskirts of Managua, Nicaragua. It consists of at least 30 volcanic structures emplaced along the NЁCS Nejapa fault, which represents the western active edge of the Managua Graben. The study area covers the central and southern parts of the volcanic field. We document the basic geomorphology, stratigraphy, chemistry and evolution of 17 monogenetic volcanic structures: Ticomo (A, B, C, D and E); Altos de Ticomo; Nejapa; San Patricio; Nejapa-Norte; Motastepe; El Hormigуn; La Embajada; Asososca; Satйlite; Refinerнa; and Cuesta El Plomo (A and B). Stratigraphy aided by radiocarbon dating suggests that 23 eruptions have occurred in the area during the past ~ 34,000 years. Fifteen of these eruptions originated in the volcanic field between ~ 28,500 and 2,130 yr BP with recurrence intervals varying from 400 to 7,000 yr. Most of these eruptions were phreatomagmatic with minor strombolian and fissural lava flow events. A future eruption along the fault might be of a phreatomagmatic type posing a serious threat to the more than 500,000 inhabitants in western Managua.http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027311002988 |

Photographs showing tephra sequences of the Managua and Las Sierras (top) and Chiltepe Formation (bottom). LCT = La Concepcion Tephra, UAT = Upper Appoyo Tephra, LAT = Lower Apoyo Tephra, FT = Fontana Tephra, CT = Chiltepe Tephra, MaT = Mateare Tephra, XT = Xiloa Tephra, UAq = Upper Apoyeque Tephra. s = intercalated paleosols and sediments. U1 and U2 are unconformities discussed in the text; U in top-left photo is an unconformity between LAT and UAT at the Apoyo crater rim. Top left: Loc. A003, Apoyo caldera rim at Diria (UTM E0603646, N1315040) showing white LAT pumice fall overlain by brown stratified phreatomagmatic fall, and UAT-1 stratified pumice fall above unconformity U. Top right: Loc. A55 in San Marcos (E0586466, N1318229) with conformable succession from FT to UAT; the unconformity (U4 in text) below LCT cannot be seen here. Bottom left: Loc. A96 at road MateareЁCNagarote (E0558032, N1355523) with succession from UAq to CT; note thin black top of zoned MaT and unconformity U2 cutting through XT. Bottom right: Loc. A116 at road MateareЁCNagarote (E0556576, N1356425) where UAq and XT overlie unconformity U1 on top of the Mateare Formation, and XT is cut by U2. The stratigraphic succession of widespread tephra layers in west-central Nicaragua was emplaced by highly explosive eruptions from mainly three volcanoes: the Chiltepe volcanic complex and the Masaya and Apoyo calderas. Stratigraphic correlations are based on distinct compositions of tephras. The total tephras combine to a total on-shore volume of about 37 km3 produced during the last ∼ 60 ka. The total erupted magma mass, including also distal volumes, of 184 Gt (DRE) distributes to 84% into 9 dacitic to rhyolitic eruptions and to 16% into 4 basaltic to basalticЁCandesitic eruptions. The widely dispersed tephra sheets have up to five times the mass of their parental volcanic edifices and thus represent a significant albeit less obvious component of the arc volcanism. Eruption magnitudes (M = log10(m) − 7 with m the mass in kg), range from M = 4.1 to M = 6.3. Most of the eruptions were dominantly plinian, with eruption columns reaching variably high into the stratosphere, but minor phreatomagmatic phases were also involved. Two phreatomagmatic eruptions, one dacitic and one basalticЁCandesitic, produced mostly pyroclastic surges but also fallout from high eruption columns. Comparison of fallout tephra dispersal patterns with present-day, seasonally changing height-dependant wind directions suggests that 8 eruptions occurred during the rainy season while 5 took place during the dry season. The tephra succession documents two major phases of erosion. The first phase, > 17 ka ago, appears to be related to tectonic activity whereas the second phase may have been caused by wet climatic conditions between 2 to 6 ka ago. The Apoyo caldera had two large plinian, caldera-forming eruptions in rapid succession about 24 ka ago and should be considered a silicic volcano with long repose times. Three highly explosive basaltic eruptions were generated at the Masaya Caldera within the last 6 ka. Since then frequent but small eruptions and lava effusion were largely limited to the caldera interior. The dacitic Chiltepe volcanic complex experienced six plinian eruptions during the last 17 ka and seems to be an accelerating system in which eruption magnitude increased while the degree of differentiation of erupted magma decreased at the same time. We speculate that the Chiltepe system might produce the next large-magnitude silicic eruption in west-central Nicaragua. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027307000686 |

Main components identified in ASOT samples. A. Juvenile, poorly vesiculated, glass shards. B ЁC D. Shallow lithic fragments (above the Upper Apoyeque Tephra): B ЁC olivine and augite bearing scoriae, C ЁC loose crystals, D ЁC hypohialine fresh basalts and andesites. EЁCF ЁC typical mid-depth lithic fragments (below Upper Apoyeque Tephra): E ЁC dacitic to rhyodacitic altered pumices, F ЁC red altered lavas and scoriae. GЁCI ЁC deep lithic fragments (Las Sierras Formation): G ЁC lithic-rich ignimbrites, H ЁC palagonitized tubular mafic pumice, I ЁC rounded hypocrystalline andesiteshttp://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027309001759 |

Main glass shards morphotypes and detailed features, typical of phreatomagmatic fragmentation. A1. Blocky-shaped ash with microstructures detailed in A2, which indicate magma fragile rupture and particle traction transport. B-1 Equant vesiculated particles with spherical bubbles, evidence of pitting and grooves structures, and adhered ash zoomed inB2. C-1. Poligonal vesiculated ash with spherical vesicles separated by thick walls and showing ash infill. Microstructures indicating fragile behavior and the effect of corrosive fluids (pits) are also common as zoomed inC2. D-1. Moss-like ash with irregular and stepped surfaces (Zoomed in D2). E-1. Equant, fused-shaped ashes without vesicles with microstructures (Detailed in E 2) that indicate a plastic behavior after fragmentation. F-1. Elongated fused-shaped ashes with adhered ash (Detailed in F2).http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027309001759 |

Composite stratigraphic successions of Late Pleistocene/Holocene tephras from highly explosive eruptions in west-central Nicaragua. Left column shows the tephra sequence after Bice (1985); right columns summarize the results of this study, regarding the Chiltepe and Managua Formations. Arrows indicate major differences with respect to Bice''s (1985) stratigraphy. Black: mafic tephras, white: felsic tephras; pointed boxes indicate observed intercalations between the two formations. Major erosional unconformities are indicated as U1 to U4.Late Pleistocene to Holocene temporal succession and magnitudes of highly-explosive volcanic eruptions in west-central Nicaragua. The stratigraphic succession of widespread tephra layers in west-central Nicaragua was emplaced by highly explosive eruptions from mainly three volcanoes: the Chiltepe volcanic complex and the Masaya and Apoyo calderas. Stratigraphic correlations are based on distinct compositions of tephras. The total tephras combine to a total on-shore volume of about 37 km3 produced during the last 60 ka. The total erupted magma mass, including also distal volumes, of 184 Gt (DRE) distributes to 84% into 9 dacitic to rhyolitic eruptions and to 16% into 4 basaltic to basalticЁCandesitic eruptions. The widely dispersed tephra sheets have up to five times the mass of their parental volcanic edifices and thus represent a significant albeit less obvious component of the arc volcanism. Eruption magnitudes (M = log10(m) − 7 with m the mass in kg), range from M = 4.1 to M = 6.3. Most of the eruptions were dominantly plinian, with eruption columns reaching variably high into the stratosphere, but minor phreatomagmatic phases were also involved. Two phreatomagmatic eruptions, one dacitic and one basalticЁCandesitic, produced mostly pyroclastic surges but also fallout from high eruption columns. Comparison of fallout tephra dispersal patterns with present-day, seasonally changing height-dependant wind directions suggests that 8 eruptions occurred during the rainy season while 5 took place during the dry season. The tephra succession documents two major phases of erosion. The first phase, > 17 ka ago, appears to be related to tectonic activity whereas the second phase may have been caused by wet climatic conditions between 2 to 6 ka ago. The Apoyo caldera had two large plinian, caldera-forming eruptions in rapid succession about 24 ka ago and should be considered a silicic volcano with long repose times. Three highly explosive basaltic eruptions were generated at the Masaya Caldera within the last 6 ka. Since then frequent but small eruptions and lava effusion were largely limited to the caldera interior. The dacitic Chiltepe volcanic complex experienced six plinian eruptions during the last 17 ka and seems to be an accelerating system in which eruption magnitude increased while the degree of differentiation of erupted magma decreased at the same time. We speculate that the Chiltepe system might produce the next large-magnitude silicic eruption in west-central Nicaragua.Key words: tephrastratigraphy, plinian eruptions. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027307000686 |

Granulometric distributions of ASOT samples and their variation with stratigraphic position (AЁCB). In general, bedsets are normally graded, with means and modes that vary from fine lapilli to coarse ash. Negative values are common in the basal bed of each bedset (NЎг-a), corresponding to coarser grain sizes, while values are close to zero or slightly positive in the middle stratified beds (NЎг-b). Standard deviations are indicative of better sorting in the basal, matrix to clast supported, fines-depleted beds of each bedset compared to the middle and rare upper, matrix supported and fine-enriched beds. Size distributions vary from symmetric to slightly asymmetric, and most of them are mesokurtic to very leptokutic. In the Walker (1971) diagram (C) plots are typical of pyroclastic surges, following Crowe and Fisher (1973), Walker (1983), Fisher and Schmincke (1984), Dellino and La Volpe (1995), Allen et al. (1996) and Genзalioрlu-Kuюcu et al. (2007).http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027309001759 |

Sketch showing the eruptions reported during the last ca. 30 ka along the southern and central parts of the NVF .The Nejapa Volcanic Field (NVF) is located on the western outskirts of Managua, Nicaragua. It consists of at least 30 volcanic structures emplaced along the NЁCS Nejapa fault, which represents the western active edge of the Managua Graben. The study area covers the central and southern parts of the volcanic field. We document the basic geomorphology, stratigraphy, chemistry and evolution of 17 monogenetic volcanic structures: Ticomo (A, B, C, D and E); Altos de Ticomo; Nejapa; San Patricio; Nejapa-Norte; Motastepe; El Hormigуn; La Embajada; Asososca; Satйlite; Refinerнa; and Cuesta El Plomo (A and B). Stratigraphy aided by radiocarbon dating suggests that 23 eruptions have occurred in the area during the past ~ 34,000 years. Fifteen of these eruptions originated in the volcanic field between ~ 28,500 and 2,130 yr BP with recurrence intervals varying from 400 to 7,000 yr. Most of these eruptions were phreatomagmatic with minor strombolian and fissural lava flow events. A future eruption along the fault might be of a phreatomagmatic type posing a serious threat to the more than 500,000 inhabitants in western Managua http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027311002988 |

The figure is not to scale. Asososca maar formation and eruptive mechanism. A. A single batch of basaltic and degassed magma rose towards the surface penetrating the Nicaragua Depression volcanic infill, favored by the NMF. At depths shallower than 190 m, according to well-log data (UNAN-CIGEO, unpublished data) there was an aquifer hosted in one or some of the scoria levels, confined between impermeable lavas. At the time immediately before the Asososca eruption, most of the Managua Formation was already deposited with the Masaya Tuff atop. B. Zoom at the contact zone, where different glassy ash morphologies resulted according to the degree of magma/water interaction, the vesicularity of magma at that locus, and depending on the different behavior of magma upon stresses generated during the contact with external water. A-type: Blocky-equant ashes derived from passive magma quenching in the contact front. BЁCC-types: Equant or pyramidal/trapezoidal ashes derived from already vesiculated magma portions that solidified prior to quenching and fragmentation. D-type: Moss-like particles were produced in zones of fluid instabilities development where magma behaved viscously during a highly efficient interaction. EЁCF-types: Fused and drop-like shapes derived from regions where surface tension effects were dominant during dynamic fluid instabilities. Particles were semi-plastic after fragmentation and prior to complete solidification. G-type: Highly vesiculated particles reflect zones of considerable gas exsolution and minimal interaction with water. H-type: Pelee-hair ashes probably reflect magma portions that did not interacted with water. CЁCD. The sudden water vaporization and expansion caused the drastic explosion, vent opening and base surges generation. C. Initially an eastern vent opened with the generation of wet base surges; the pre-existence of a surface lake probably contributed to the initial high water/magma ratio. D. As the lake got empty, the low-storage aquifer favored the generation of dominantly dry base surges and the migration of the vent westward. E. Subsequently an irregular, bowl-shaped maar crater was formed as dry base surges continued, accompanying wall-rock collapses, vent coalescence, and minor deepening occurred.http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027309001759 |

A broad expanse of youthful lava flows extends across the floor of Nicaragua''s Masaya caldera, whose wall forms the arcuate rim in the background. The lava flows originated from the post-caldera cones of Masaya and Nindirн and constrain Lake Masaya against the eastern caldera wall. Recent lava flows have flooded much of the caldera and have overflowed its rim in one location on the NE side. This view from the NW shows Mombacho volcano in the distance. The sparsely vegetated lava flow in the foreground was emplaced during an eruption in 1772. The flow originated from a vent on the north side of Old Masaya crater and traveled to the north. One lobe passed through a notch in the northern caldera rim, while the lobe seen in this photo was deflected by the caldera rim and traveled to the SE into Lake Masaya, which is ponded against the SE caldera rim. The twin-peaked stratovolcano in the distance is Mombacho volcano.Photo by Jaime Incer. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

An aerial oblique photo from the NW shows the summit crater complex of Masaya volcano. The wall of the 6 x 11 km wide caldera inside which the central cone complex was constructed can be seen at the upper right and the extreme upper left (where it contains Lake Masaya).Aerial photo by Instituto Geogrбfico Nacional, 1975 (courtesy of Jaime Incer). http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

Masaya is a shield volcano located 20 km south of Managua The volcanic complex is composed of a nested set of calderas and craters, the largest of which is Las Sierras shield volcano and caldera. Within this caldera lies Masaya Volcano sensu stricto, a shallow shield volcano composed of basaltic lavas and tephras. This hosts Masaya caldera, formed 2500 years ago by an 8-km3 basaltic ignimbrite eruption. Inside this caldera a new basaltic complex has grown from eruptions mainly on a semi-circular set of vents that include the Masaya and Nindiri cones. The latter host the pit craters of Masaya, Santiago, Nindiri and San Pedro. Observations in the walls of the pit craters indicate that there have been several episodes of cone and pit crater formation.The floor of Masaya caldera is mainly covered by poorly vegetated aa lava, indicating resurfacing within the past 1000 or so years, but only two lava flows have erupted since the sixteenth century. The first, in 1670, was an overflow from the Nindiri crater, which at that time hosted a 1-km-wide lava lake. The other, in 1772, issued from a fissure on the flank of the Masaya cone. Since 1772, lava has appeared at the surface only in the Santiago pit crater (presently active and persistently degassing) and possibly within Nindiri crater in 1852. A lake occupies the far eastern end of the caldera.Masaya continually emits large amounts of sulfur dioxide gas (from the active Santiago crater) and volcanologists study this (amongst other signs) to better understand the behavior of the volcano and also evaluate the impact of acid rain and the potential for health problems.Although the recent activity of Masaya has largely been dominated by continuous degassing from an occasionally lava-filled pit crater, a number of discrete explosive events have occurred in the last 50 years. One such event occurred on November 22, 1999, which was recognised from satellite data. A hot spot appeared on satellite imagery, and there was a possible explosion. On April 23, 2001 the crater exploded and formed a new vent in the bottom of the crater. The explosion sent rocks with diameters up to 60 cm which travelled up to 500 m from the crater. Vehicles in the visitors area were damaged and one person was injured. On October 4, 2003 an eruption cloud was reported at Masaya. The plume rose to a height of ~4.6 km.The Masaya is one of 18 distinct volcanic centers that make up the Nicaraguan portion of the Central American Volcanic Belt (CAVF). Formed by the subduction of the Cocos Plate beneath the Caribbean Plate, along the Mesoamerican trench, the CAVF runs from volcan Tacana in Guatemala to Irazu in Costa Rica. In western Nicaragua, the CAVF bisects the Nicaraguan Depression from Cosiguina volcano in the northwest to Maderas volcano in Lago Nicaragua. The Interior highlands to the northeast make up the majority of Nicaragua. Western Nicaragua consists of 4 principal geological provinces paralleling the Mesoamerican trench: 1. Pre-Cretaceous to Cretaceousophiolitic suite; 2. Tertiarybasins; 3. Tertiary volcanics; and the 4. Active Quaternary volcanic range.An ophiolitic suite is found in the Nicoya Complex, which is made up of cherts, graywackes, tholeiiticpillow lavas and basaltic agglomerates. It is intruded by gabbroic, diabasic, and dioritic rocks. The Cretaceous-Tertiary basin is made up of five formations of mainly marine origin. The Rivas and Brito formations are uplifted to the southeast and are overlain in the northwest by a slightly tilted marine near- shore sequence, the El Fraile formation. This in turn passes north into the undeformed Tamarindo formation, a sequence of shallow marine, lacustrine and terrestrial sediments interspersed with ignimbrites. Northeast of the Nicaraguan Depression, the Coyol and Mataglapa formations, run from Honduras to Costa Rica and still show evidence of some volcanic centres, distinguishable as constructional landforms.Quaternary volcanic rocks are found mainly in the Nicaraguan Depression and form two major groups: the Marrabios and Las Sierras formations. The Marrabios Cordillera starts in the northwest with Cosiguina volcano and continues to the southeast with San Cristobal, Casita, La Pelona, Telica and Rota. El Hoyo, Monte Galan, Momotombo and Momotombito volcanoes are built upon ignimbrite deposits from the nearby Malpaisillo caldera. South-east of Lake Managua lie Chiltepe, the Nejapa alignment, Masaya, Apoyo and Mombacho which overlie the Las Sierras ignimbrites, erupted from the Las Sierras Caldera surrounding Masaya volcano. Further south in Lake Cocibolca (or Lake Nicaragua), Zapatera, Concepcion and Maderas volcanoes mark the end of Nicaraguan section of the CAVF.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masaya_Volcano |

The Masaya central cone complex within the Holocene Masaya caldera (foreground) lies within a larger Pleistocene caldera, the Las Sierras (or Las Nubes) caldera, which was formed following the eruption of a major ignimbrite about 30 KA. The ignimbrite deposit from this eruption is found in the Managua area, where it is cut by faults of the Managua Graben, which extends to the north, constraining the SE margins of Lake Managua. Masaya is one of Nicaragua''s most unusual and most active volcanoes. Masaya lies within the massive Pleistocene Las Sierras pyroclastic shield volcano and is a broad, 6 x 11 km basaltic caldera with steep-sided walls up to 300 m high. The caldera is filled on its NW end by more than a dozen vents that erupted along a circular, 4-km-diameter fracture system. The twin volcanoes of Nindirн and Masaya, the source of historical eruptions, were constructed at the southern end of the fracture system and contain multiple summit craters, including the currently active Santiago crater. A major basaltic plinian tephra was erupted from Masaya about 6500 years ago. Historical lava flows cover much of the caldera floor and have confined a lake to the far eastern end of the caldera. A lava flow from the 1670 eruption overtopped the north caldera rim. Masaya has been frequently active since the time of the Spanish Conquistadors, when an active lava lake prompted attempts to extract the volcano''s molten "gold." Periods of long-term vigorous gas emission at roughly quarter-century intervals cause health hazards and crop damage. Masaya is one of Nicaragua''s most unusual and most active volcanoes. It is a broad, 6 x 11 km basaltic caldera with steep-sided walls up to 300-m high. The caldera is filled on its NW end by more than a dozen vents erupted along a circular, 4-km-diameter fracture system. The twin volcanoes of Nindirн and Masaya are seen here from the east caldera rim above Lake Masaya. Masaya has been frequently active since the time of the Spanish Conquistadors, when an active lava lake prompted several attempts to extract the volcano''s molten "gold." Photo by Jaime Incer, 1990 http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

Masaya (left) and Nindirн (right) cones are seen here from the NW across the floor of Masaya caldera. Santiago crater, the source of most of Masaya''s historical eruptions, lies in the saddle between the two cones. Historical and prehistorical lava flows blanket the caldera floor.Photo by Jaime Incer, 1990.http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

Nindiri crater is partially truncated by the walls of Santiago crater, which formed in 1858-1859. The crater walls reveal flows from lava lakes erupted between 1524 and 1670. An active lava lake was apparently present in Nindirн crater from 1524 to 1544, as reported by Spanish Friars passing through Nicaragua. The Spanish chronicler Oviedo observed the lava lake when he climbed the volcano in July 1529. In 1534 Friar Bartolomй de las Casas reported that a letter could be read at night in the town of Nindirн (6 km away) by the glow of lava. Photo by Jaime Incer, 1991.http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

Santiago crater, seen here from the NE, formed in 1853. A strong detonation on April 9, 1853 was followed by heavy gas emission with no noticeable ejection of pyroclastic material. Flames were seen at the summit of the volcano on the night of September 15 from the town of Masatepe and later investigation revealed a new 80 x 65 m wide crater (later known as Santiago) with incandescent lava surrounded by volcanic bombs. Santiago pit crater expanded significantly in 1858-1859 and is now 600 m wide. Santiago crater was initially formed in 1853, but the present pit crater formed during the 1858-1859 eruption. A column of flames and ash eruptions were reported on January 27 and March 27, 1859 accompanied by collapse of Santiago and San Pedro Craters. After its initial collapse, Santiago pit crater was a vertical cylinder about 150 m deep and 600 m across. By the time of the 1865 visit of Seebach, the craters had evolved to their present configuration. Photo by Jaime Incer, 1996.http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

Masaya 11.98 N, 86.16 W summit elevation 635 m caldera. Masaya is a basaltic volcano located 25 km southeast of Managua, Nicaragua. It consists of a 6Ч11.5 km diameter caldera, which formed by a series of Plinian eruptions in the past 6000 years. A lava lake has formed in the crater on numerous occasions.2008 Eruptions. An eruption of ash from Masaya volcano occurred on 29th April 2008, rising to a height of 2.1 km. Ash emissions occurred in September, November and December 2008.2006 Eruptions: Two small phreatomagmatic eruptions occurred at Masaya volcano on 4th August 2006. Incandescence was visible at the bottom of the crater, and sounds similar to a jet engine were heard. In October 2006 a new vent opened on the floor of Santiago crater with a small lava lake which displayed intense degassing. Following heavy rains, landslides occurred from the crater walls.2001 Eruptions: On 23rd April 2001 tourists were caught in one of the most powerful eruptions at the volcano in 30 years. Two people were injured and 200 people were caught in the danger zone. Volcanic bombs landed in the parking area, damaged cars and set fire to vegetation and shelters. Scientists had left the crater only one hour before Masaya erupted. 2000 Eruptions:On 6th January 2000 a small explosion occurred at Santiago crater.1996 Eruption: A strombolian eruption occurred at Masaya volcano on 5th December 1996 which ejected blocks up to 10 cm in diameter.1993 Lava Lake: A lava lake formed in the bottom of Santiago crater in late June 1993 after an absence of 3 years.Masaya Volcano Eruptions 2008, 2006, 2005, 2003, 2001, 1999-2000, 1996, 1993-94, 1989, 1987, 1965-85, 1946-47?, 1919-24, 1913, 1906, 1904, 1902-03, 1858-59, 1858?, 1856-57, 1853, 1852, 1772, 1670, 1613?, 1586?, 1570, 1551, 1524-44? http://www.volcanolive.com/nicaragua.html |

Steep-walled Santiago crater provides a dramatic perspective into the vent of an active volcano. The crater floor is covered by recent lava flows and fume rises from an inner crater. The walls of the 600-m-wide crater expose stacked lava flows, truncated lava lakes, and pyroclastic material erupted from earlier vents. Photo by Jaime Incer. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

Masaya National Park |

A tumulus on the surface of a pahoehoe lava flow in the foreground is exposed on the western flank of Masaya volcano, with Nindirн cone rising in the background. Nindirн is the westernmost cone of Masaya''s summit complex and is cut by a large summit crater not apparent from this vantage point. Photo by Jamie Incer. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

A small eruption occurred from Santiago crater on February 15, 1987 following blockage of the vent by landslides in November and December 1986. The small eruption ejected ash and blocks, which fell back into the bottom of the vent. Additional collapses took place on February 20, and the circular vent continued to produce small eruptions after February 22. This photograph of Santiago''s inner crater (180 m in diameter and 72 m deep) was taken after the collapse events of late 1986 and early 1987. Photo by Douglas Farjado, 1987 (INETER). http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

Fume rises in 1978 from a vent on the floor of Santiago crater, seen here from its SE rim. The floor of the crater is covered by fresh lava flows erupted between 1965 and 1972. A lava lake was present on the part of the crater floor until 1979, and intermittent explosive activity continued until 1985.Photo by Jaime Incer, 1978. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

The 1670 lava flow covering much of this photo originated from Nindirн crater on the horizon. A lava lake in the crater eventually overflowed the rim, producing a lava flow that traveled from Nindirн crater for 5 km down the northern flank of Masaya''s post-caldera cone. Some accounts confused the 1670 flow from Nindirн with the 1772 flow from Old Masaya crater.Photo by Jaime Incer, 1994.1996. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

Masaya volcano is noted for long-duration periods of voluminous gas emission. This February 1982 photo from the NE shows a gas plume pouring from Santiago crater, during the 4th gas emission crisis of the 20th century. Emission of a very large gas plume had continued without interruption since the fall of 1979. Remote sensing of SO2 revealed continued high level flux, with a 1500-2000 tons/day average during 1980. Distribution of the gas plumes by prevailing winds caused widespread crop damage.photo by Dick Stoiber, 1982 (Dartmouth College). |

Incandescent magma is visible in 1996 at the bottom of Santiago crater from a vent below the south crater wall. A small strombolian eruption on December 5, 1996 ejected blocks (<10 cm in diameter), ash, and Pele''s hair. Some of the inner crater walls collapsed, partly closing the incandescent vent. Prior to this eruption the vent''s gas temperature was 1,084°C; afterwards, it dropped to 360°C. Photo by Jaime Incer, 1996. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

An incandescent vent glows on the floor of Santiago crater in July 1972. A new lava lake formed in Santiago crater in October 1965. By 1969 activity was restricted to a small spatter cone; after it collapsed in 1972 a lava lake was visible until 1979. Periodic lava lake activity has occurred since the time of the Spanish Conquistadors. The partially yellow incandescence of the active lava lake was taken for molten gold, prompting several attempts to mine it.Copyrighted photo by Dick Stoiber, 1972 (Dartmouth College). http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

A new lava lake appeared on the floor of Santiago Crater in October 1965, marking the beginning of Masaya''s third 20th-century lava-lake cycle. By 1969 activity was restricted to a small spatter cone in the center of the crater. Several lava flows erupted on the crater floor between 1965 and 1972. The spatter cone collapsed in 1972 and lava lake activity was visible until 1979, when activity subsided and was followed by dense gas emissions. Small ash eruptions took place on single days in 1981, 1982, 1984, and 1985.Photo by Jaime Incer. http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

An October 1971 photo from the crater rim shows a fresh black lava flow extruded onto the crater floor. Fumaroles rise from the surface of the flow at the right. Masaya began a long-duration eruptive period in 1965. Several lava flows, such as this one, were erupted between 1965 and 1972. An active lava lake was visible until 1979, and intermittent small explosive eruptions lasted until 1985.Photo by Bill Rose, 1971 (Michigan Technological University). http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

A vigorous gas plume is seen exiting from Masaya volcano in November 1998. Masaya''s latest episode of degassing activity began in mid 1993. Prevailing winds typically distribute plumes from Masaya to the west, where they come in contact with the higher-elevation Las Sierras highlands (left horizon). The volcanic emissions during 1998-1999 affected a 1250 sq km area downwind, causing health hazards and extensive vegetation damage, resulting in economic losses to coffee plantations. Photo by Lee Siebert, 1998 (Smithsonian Institution). http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/volcano.cfm?vnum=1404-10=&volpage=photos |

A vigorous steam plume pours from Masaya volcano in this November 9, 1984 Space Shuttle image taken near the end of a two-decade-long eruptive episode. North lies to the lower right, with Lake Nicaragua at the lower left and Lake Managua at the lower right. To the left of the plume from Santiago crater is Lake Masaya (ponded against the rim of Masaya caldera) and the circular lake-filled Apoyo caldera. The two caldera lakes at the lower right are Apoyeque (light blue) and Jiloa (dark-colored), across the bay from the city of Managua.Photo by National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA), 1984. |

Apoye caldera, Laguna de Apoyo (Apoyo Lagoon), Crater Lake, last eruption about 23,000 years ago, 468m,When the old Apoyo Volcano erupted, about 23,000 years ago, it left a huge 7 km-wide crater that gradually filled with water. This lake, located between Masaya and Granada, is surrounded by the old crater wall. This spectacular lagoon can be easily reached by car, and it is a great spot for swimming and relaxing. There is still an active fumarole at the western shore of the lagoon, so the volcano is not yet dormant. There are also myths that still surround this pristine lagoon.Granada, 11.92 N, 85.98 W, summit elevation 300 m, Fissure vents. Granada Volcano is located western Nicaragua, on northwestern shore of Lake Nicaragua (Cocibolca). The volcano lies next to Granada, the oldest city founded by Europeans on mainland America. La Joya explosions craters are located SW of Granada. Apoyo Caldera Apoyo caldera lies along the NW-trending chain of Quaternary volcanoes in western Nicaragua between Lakes Managua and Nicaragua. The caldera is nearly circular (approximately 7.0 X 6.5 km in diameter) with a depth of at least 600 m below the west rim. Lake Apoyo occupies the caldera. The caldera lies on the western rim of the Nicaraguan Depression. The depression consists of a broad, shallow graben trending northwest between parallel sets of faults.Volcanism and faulting within the graben are caused by the northeastward subduction of the Cocos Plate beneath the Caribbean Plate along the Middle American Trench.Caldera collapse.Caldera collapse occurred at Granada volcano 23,000 years ago with the eruption of 11 cubic km of magma in the form of airfalls, ash-flows and pyroclastic surges over two separate phases. The pumice deposits associated with Apoyo caldera collapse represent the largest eruption of silicic magma from any Nicaraguan volcano during Quaternary time. Current and Future Activity Granada volcano is currently inactive, with only a few small hot springs and areas of hot ground located at the western edge of the caldera lake. There has been a long history of activity at the volcano, and the age of the most recent eruptions indicates that the Granada magmatic system is not dead and that future eruptions are possible. The city of Granada, is built upon a thick deposit of ignimbrite, and is likely to be directly in the path of another ashflow eruption, if it occurs. http://www.volcanolive.com/nicaragua.html |

Mombacho is a stratovolcano on the shores of Lake Nicaragua that has undergone edifice collapse on several occasions. Two horseshoe-shaped craters cut the summit on the NE and south flanks, modifying the profile of the volcano. The NE-flank scarp, whose NE wall forms the left skyline, was the source of a large debris avalanche that produced an arcuate peninsula and the Las Isletas chain of islands in Lake Nicaragua. The only reported historical activity was in 1570, when a debris avalanche destroyed a village on the south side of the volcano. |

Mombacho is a stratovolcano 1344 metres high, the Mombacho Volcano Nature Reserve. Mombacho is an active volcano but the last eruption occurred in 1570. There is no historical knowledge of earlier eruptions. The highest regions of the volcano is home to a cloud forest and dwarf forest, which contains flora and fauna that are endemic purely to the volcano. The more difficult trail is the only way to see some features such as the dwarf forest. There are more than 700 different plants registered around Mombacho. Included are many species of orchids. Mombacho is an andesitic and basaltic stratovolcano on the shores of Lake Nicaragua south of the city of Granada that has undergone edifice collapse on several occasions. Two large horseshoe-shaped craters formed by edifice failure cut the summit on the NE and southern flanks. The NE-flank scarp was the source of a large debris avalanche that produced an arcuate peninsula and a cluster of small islands (Las Isletas) in Lake Nicaragua. Two small, well-preserved cinder cones are located on the volcano''s lower northern flank. The only reported historical activity was in 1570, when a debris avalanche destroyed a village on the south side of the volcano. Although there were contemporary reports of an explosion, there is no direct evidence that the avalanche was accompanied by an eruption. Fumarolic fields and hot springs are found within the two collapse scarps and on the upper northern flank.Mombacho volcano is a 1,345-m-high stratocovolcano located about 10 km south of the city of Granada. Lake Nicaragua is located to the east and Apoyo Caldera a few kilometers to the north-west.On the north and south of the summit there are two collapse amphitheatres. A third avalanche deposit is located southeast of Mombacho volcano.A lava flow which enters Lake Nicaragua forms a cluster of islands known as Las Isletas. The area has been declared a natural park and contains 50 species of mammals, 174 species of birds, 30 of reptiles and 750 species of flora. - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mombacho |

The south side of Mombacho volcano contains a horseshoe-shaped crater that was the source of a large debris avalanche in 1570 AD that swept over a village south of the volcano, killing 400 persons. The avalanche traveled 13 km to the south; contemporary accounts note that if it had occurred to the north, it would have reached the city of Granada. Contemporary accounts indicate that the volcano "exploded," but eruptive activity associated with the collapse has not been documented.Photo by Jaime Incer. http://www2.brevard.edu/reynoljh/centralamerica/nicaragua.htm |

These angular boulders are part of a debris-avalanche deposit that originated from the south side of Mombacho volcano (seen in the background), most likely in 1570 AD..Photo by Jaime Incer, 1972.http://www2.brevard.edu/reynoljh/centralamerica/nicaragua.htm |

Mombacho volcano in the background collapsed during the late Pleistocene, producing a debris avalanche that swept into Lake Nicaragua, deposting debris that accumulated to form the Aseses Peninsula in the foreground. The surface of the avalanche deposit lies below the lake surface immediately offshore of the mainland, creating the Bay of Aseses in the middle of the photo. Portions of the deposit rise above the lake surface, forming hundreds of small islands.Photo by Jaime Incer..http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mombacho |